Shane Dowd, CES CMP

(has hip impingement)

Femoroacetablular Impingement (FAI) is a common issue that causes hip tightness and pain, which ultimately restricts movement. We’ve wanted to address this topic for a while, and Shane stepped in to provide probably the most comprehensive guide you could possibly ask for. Enjoy!

In this article you will learn how to fix hip impingement (femoroacetabular impingement) without surgery.

In fact…

These are the same strategies I used to fix my own hip impingement in 2011.

You will also discover what I learned from spending $25,837.29 on physical therapy (and other treatments) so you can select the best treatment for you.

Let’s dive right in!

Table of Contents:

- What is Hip Impingement?

- The Hidden Story of Hip Impingement

- How To Tell If You Have Have Hip Impingement?

- How To Fix Hip Impingement (Treatment Options)

- The Best Approach for Hip Impingement

- How Long Does it Take to Recover from Hip Impingement?

- The Nerdy Science of Hip Impingement

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Hip Impingement

- Summary & Action Steps to Fix Hip Impingement

👉 Get our hip mobility routine so you can loosen up your hips whenever and wherever you need to.

What is Hip Impingement?

The theory of hip impingement goes something like this…

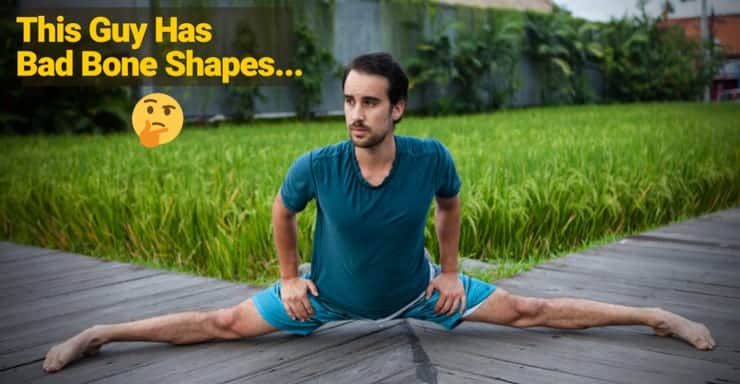

If you have “bad bone shapes” that means you have femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). A Google search for “hip impingement” will probably find you a definition such as:

“…a condition where the bones of your hip joint come too close and pinch tissue or cause too much friction.”—Stanfordhealthcare.org

In short, theoretically, “bad bone shapes = big hip problems.”

BUT this is not the whole story…

The Hidden Story of Hip Impingement

For many years doctors have claimed that FAI is exclusively a bone problem. “If you have bad bones shapes you will have FAI,” they say.

This is what I was told when I got an XRAY and MRI that showed I had:

- FAI (cam impingement)

- a paralabral cyst

- labral damage

Here’s a report on the X-ray and MRI I got:

It turns out, while bone problems are a common cause, there is an additional reason for hip impingement.

Bone Reasons for Hip Impingement

There are three types of bone “deformities” in hip impingement:

- Cam impingement—occurs when the head of the femur is too thick or has bumps and cannot fit well into the socket

- Pincer impingement—occurs when the rim of the socket, or acetabulum, has extra bone which also causes the head of the femur to not fit well into the socket.

- Mixed Impingement—when a person has a mix of these types of bone shapes.

But what if you have “bad bone shapes” and NO pain? Actually, this is more common than you might expect. Take myself for example:

In 2011 I had lots of hip pain and movement problems… but now I no longer do. What gives?

What gives is… I learned how to optimize everything else (my muscles, movement, and lifestyle). I still have “bad bones.” But even though my bones are poorly shaped, they are, after all, ball and socket joints. Ball and socket joints can have incredible range of motion… even if they aren’t perfectly smooth and spherical.

So why doesn’t everyone have “incredible range of motion”?

Well… the bones are just one factor.

Most people think the bones account for 90% of a person’s mobility potential, but this is false. The hips also become limited because of tendons, ligaments, muscles, and more. If you have “bad bones,” the hips may still have the potential for incredible range of motion… if you learn how to train properly.

The summary is this: research (and experience) shows the bone shapes are NOT the only reason hips hurt or are limited in motion. The bones matter, of course, but they are not the only determinant of hip joint health and mobility.

Muscular Reasons for Hip Impingement

The muscular reasons for FAI fall into three categories, and it is possible to have problems in any (or all) of these categories:

- Muscle flexibility

- Muscle tissue quality

- Muscle activation (or lack thereof) and motor control

This video + animation explain the muscular theory of hip impingement:

The summary is this: muscles that are too tight, too weak, or full of knots and trigger points can cause a joint to be out of position and cause impingement. In fact, the feeling of “impingement” is often just the muscles themselves and not the joint.

The fact that muscles matter shouldn’t surprise anyone. If you don’t stretch, strengthen and massage your body, it won’t function well—duh!

It’s just like a car that never visits the mechanic for a tune-up!

How to Tell if You Have Hip Impingement

Hip impingement can manifest in many ways (not just pain in the hip.)

Hip impingement can manifest in many ways (not just pain in the hip.)

I’m going to go over a few symptoms and tests you can do to see if you have hip impingement. Afterward, I’ll show you how to fix it.

NOTE: These are NOT tests to tell if you have “bad bone shapes.”

In fact, modern scientific research on FAI draws a distinction between “FAI bone shapes” and “FAI syndrome.” The studies show that you can have FAI syndrome (pain/movement problems) and NOT have “bad bones.”

So, if you fail one of the following hip impingement tests or experience some of these symptoms, don’t be scared that you are doomed for life!

You’re not!

These are just general tests for pain/mobility in your hips. Use these tests as a starting point for what you might need to work on.

Here are symptoms that you may feel in daily life:

- Stiffness in the thigh, hip, or groin

- The inability to flex the hip past 90 degrees

- Pain during hip flexion and internal rotation

- Pinching or aching in the front hip, groin, or outer hip

The symptoms can manifest in various ways.

The pinching can be sharp or dull, hard or soft. It can even be more like a constant throbbing in the hips (groin/glute, etc). Sometimes symptoms show up NOT in the hip, but in the low back or SI joint (as was the case for me). Sometimes the symptoms show up as early warning signs in the gym. Sometimes there is no (or minimal) pain but your hip joint is very restricted.

In short, pain or tightness in the hips or nearby areas are an indicator that “something’s off” and you’ll want to work to improve it.

Of course, it’s not a conclusive diagnosis, but it is a warning sign from your body saying: “Hey! Pay attention to me!”

4 Hip Impingement Tests: Do You Pass?

Here are some tests that you can perform on yourself to see if you have hip impingement or hip impingement symptoms.

There are also many other functional ways to assess how your hips move and feel. Don’t think that these tests are the only valid ones.

You may find sources that insist that these tests be done by a professional to truly examine whether you have impingement. Of course, while another person can be helpful, you are dealing with your own body. You move your body and you have the capability to decide whether you feel discomfort in the form of hip impingement. It is not all that complicated.

- If you are feeling discomfort or pain in a movement, then you know you fail that test and will want to work on improving that movement.

- If your muscles cramp at end-range when performing these tests this is not hip impingement. It’s your muscle cramping. Relax and test again. If you continue to cramp then your muscles are not used to the movement.

- Lastly, all tests should be done with both legs, but for the sake of simplicity, I will only specify the test with your right leg.

1. Active Hip Flexion

- Stand on one leg with the leg completely straight. Relax and breathe. Actively raise your right leg into hip flexion as far as you can and keep your right knee bent at 90 degrees.

- Leave your left leg relaxed. Try not to rotate your right leg internally or externally. Just keep it straight. Your left leg may flare in, out, or stay neutral depending on your muscle balances. This is not important for this test.

- If you can bring your leg up to 110-120 degrees from the floor without pinching or discomfort then you passed the test. If not, then it’s a fail.

2. Passive Hip Flexion:

- Repeat the steps from the active hip flexion test, but instead of actively raising your leg, passively raise your leg into hip flexion. Do this by picking up your own leg with your arms and moving it into hip flexion.

- Again, 110-120 degrees from the floor without pinching or discomfort is a pass. Anything less is a fail.

Expect slightly more range of motion in passive hip flexion.

3. Active and Passive Hip Internal Rotation

- Lie on your back on the floor. Bring your right leg up to 90 degrees of hip flexion. Keep your right knee bent at 90 degrees as well.

- Now internally rotate your right leg so that your right foot moves away from the midline of your body. If you can internally rotate your leg 30-45 degrees then you pass.

- The same can be done passively by manually moving your leg or having someone else help.

4. Hip External Rotation

- Lie on your back on the floor. Bring your right leg up to 90 degrees of hip flexion. Keep your right knee bent at 90 degrees as well.

- Now externally rotate your right leg so that your right foot moves toward and over the body. If you can externally rotate your leg 45 degrees then you pass. The same can be done passively.

Note: You can do all of the “active tests” passively (if you have a therapist, coach, partner to help you.) Both passive and active tests will teach you something about your hips.

👉 Get our hip mobility routine so you can loosen up your hips whenever and wherever you need to.

How to Fix Hip Impingement (Treatment Options)

So, if you failed any of the above tests, what are your treatment options? There are 3 standard approaches:

- Physical therapy

- Surgery

- Injections

Physical Therapy (PT) for Hip Impingement

I’ve spent over $25,837.29 out of pocket trying to fix my own FAI.

In this journey I discovered that there are good PTs and there are bad PTs. Good rehab centers and bad rehab centers. Good exercises and bad exercises. Overall I felt my treatments to be missing something…

I found that most PT programs are lacking in 5 key areas:

- Time (usually only 15-20 mins with the therapist)

- Homework (not enough to do more than symptom relief)

- Theoretical vs Experiential (most PT’s haven’t had FAI themselves)

- Systems Approach (many programs completely skip 1 or more of the 3 pillars that help FAI. More about that in the “TSR” approach below.

- Poor exercise-selection (often the exercises chosen can make problems worse.)

So do I think PT for hip impingement is worthless? Absolutely not!

Like any profession, there are good practitioners and there are bad practitioners. There are practitioners with direct personal experience with FAI and those who have only read about it in a textbook.

Often it’s not the PT’s fault. It’s the system itself.

The typical physical therapy model of 15-20 minutes with the PT and 5-10 exercises to do at home simply will not cut it. That is not an attack on physical therapists, but rather on the system they’re working within.

In this article, I show you how to find a good PT (and there are many brilliant PTs out there!). I highly recommend finding one to complement the work and exploration you are doing on your own.

The summary is this: If you’re looking to restore pain-free motion in your hips over the long term, physical therapy can be helpful, but it might be incomplete. In the end, you need to take responsibility for becoming your own best therapist.

Surgery for Hip Impingement

In a surgery for hip impingement, the surgeon will cut bone off of your femoral head, acetabulum, or both. In the more extreme surgeries, your entire hip is replaced. In other words, surgery is quite a drastic treatment option.

While the recovery process is long, these surgeries are supposed to increase range of motion and get rid of pain.

Unfortunately, the success of these surgeries is not what one would expect. In some cases surgery may actually make the hips WORSE. Even with less drastic surgeries (hip arthroscopy) many people report that the surgery relieved some of the pain but not all of it. (Just search “failed hip surgery” in any of the online FAI support groups.)

But wait… If the standard theory is that “bad bones” cause pain, and the excess bone is gone, then how does pain persist? Are you starting to see that the body is a bit more complicated than that?

To be clear: I am not arguing that PT and surgery have no place—they absolutely do!

…but who should be the first line of defense when you have hip impingement? Taking control of your own body and trying a few lifestyle changes and at-home exercises? Maybe even doing this with the help of a qualified PT?

OR a risky, invasive, $8,000+ surgery (plus hospital expenses and months long rehab expenses after)?

To me the hierarchy is clear:

- Less invasive before more invasive

- Less expensive before more expensive

Of course, there are some cases where surgery is helpful. I’m just arguing that it shouldn’t be the first, second, or even third option. For some people who have truly “maxed out” the nonsurgical options, surgery can be a last resort that does make a difference.

Just make sure you start with cheaper, less risky options first.

Injections for Hip Impingement

Intra-articular steroid injections can be used to reduce pain and improve hip function. However, the effects of these are temporary.

Many doctors and surgeons assume that intra-articular injections help diagnose that the problem is in the joint, but this too seems to be a poor assumption.

The issue with all these treatments is that the patient does not learn any techniques to prevent, and/or address any future hip issues as they arise. They just want hope and pray that a pill, an injection, or a one-time “quick fix” surgery will be their ultimate savior.

Unfortunately, that’s not how life works.

We get hundreds of emails a week from people with hip problems, and some people do report that they got some temporary pain relief from the injections. However, the majority end up telling us that it did nothing or was short lived. Some research is even showing potential adverse effects of joint injections.

In summary, hip injections are probably not something to bet all your money on.

The Best Approach for Healing from Hip Impingement

The best approach for hip impingement combines the best strategies from modern science with unique and innovative exercises NOT found in traditional rehab programs.

It’s also important that this approach comes from real life experience (not textbook theory).

As you can see, I’ve been where you’re at (with lots of hip pain). And there is hope.

The FAI Fix is based on personal experience and the experience we have gained in developing a system that is helping thousands of people with this specific problem since 2015.

We call this the TSR System, which stands for: Tissue Work, Stretching, and Reactivation.

Tissue work

Tissue work is as close to a “magic pill” for immediate pain relief/mobility improvement that I’ve found. Especially for athletes or people with a bit more muscle bulk and immobility.

Tissue work is as close to a “magic pill” for immediate pain relief/mobility improvement that I’ve found. Especially for athletes or people with a bit more muscle bulk and immobility.

Tissue work involves massaging muscles (in a highly specific way) to restore tissue quality, reduce pain, and improve range of motion.

In a sedentary or athletic lifestyle, muscles get stiff. They get dense and stuck together. Massage is a way to restore suppleness to the muscle. It sounds simple, but the depth to which one can perform tissue work is highly underrated.

This kind of “massage” (targeted tissue work) is much deeper, and much more effective than normal massage or simple foam rolling.

Most physical therapy programs omit this modality completed or don’t apply it judiciously. This is a huge mistake. Adding in tissue work can make the biggest difference in healing FAI.

Stretching

When muscles get tight (which can happen in a sedentary or athletic lifestyle), they need to be stretched. Stretching is a part of the TSR method because it is the main way to restore a muscle to its normal length.

When muscles get tight (which can happen in a sedentary or athletic lifestyle), they need to be stretched. Stretching is a part of the TSR method because it is the main way to restore a muscle to its normal length.

As a rule of thumb, if you are not very flexible, then you probably need to stretch. But which muscles do you need to stretch?

Answer: All of them.

All muscles of the hip: quads, hamstrings, adductors, glutes, and hip flexors can tighten up and cause FAI symptoms. Over time, you will learn which muscles you need to stretch more or less.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, someone who is hypermobile (too flexible) may want to concentrate more on the reactivation part of the TSR method. If you are this type of person, you need to learn what to do if stretching doesn’t work.

As for everyone else, experiment with your tight areas and start stretching.

Reactivation/Reeducation

Reactivation means “waking up” sleep muscles.

When muscles are not used they become “dumb” (poor motor control), atrophied, and weak. This is often called muscle amnesia.

Watch this video to learn a few ways to activate your muscles:

Muscles may be under-active or “asleep” for a variety of reasons:

- The most common reason is a sedentary lifestyle. When people sit all their lives, muscles turn off and range of motion (ROM) decreases.

- Another reason is overdoing the same movement pattern. For example, playing soccer seven days a week and developing muscle imbalances.

- Another reason muscle amnesia can occur is faulty motor control (how skillfully or unskillfully you are moving your body).

Muscle & movement reeducation can address these imbalances.

For example, the glutes or hip flexors may be weak and inactive when it comes to a squat. If a person cannot feel the glutes or hip flexors helping in the movement, they may be weak and inactive.

Glute bridges or hip flexor activation, combined with practicing the squat can be prescribed to begin to fix this.

Muscle reactivation is not just about doing a million glute bridges until you are blue in the face. Sometimes you need to “release the brakes” through stretching to allow a muscle to “wake up.”

By the way, this is one of the paradoxes with hip impingement:

- Do I need to stretch or strengthen my hip flexors?

- Do I need to stretch or strengthen my glutes?

The answer is: maybe both!

Anterior Pelvic Tilt, Posture, and Lifestyle

Another part of “re-education” is the way you are living your life.

Another part of “re-education” is the way you are living your life.

Aside from fixing the tissue quality, length, and strength of your muscles, posture and lifestyle need to be addressed to heal FAI. Posture affects FAI in one common scenario: anterior pelvic tilt.

Anterior pelvic tilt (APT) is when the pelvis tilts forward excessively. It makes you look like you’re sticking your butt and your belly out too much. This is a problem when it comes to FAI because it causes your femurs to run into your pelvic bone too early when squatting or hip hinging.

Training your core to realign your pelvis and posture will help in the FAI recovery process. If you also do tissue work, stretching and strengthening, you will accelerate the correction of APT.

But, if it’s not supported with lifestyle changes (the other 23 hours of the day), you will be taking two steps forward and two steps back.

How do you sit? How much do you sit? How do you sleep? How active are you?

All these factors need to be addressed complement the TSR work.

Here are some quick tips:

- The 30/3 Rule: Sit for 30 minutes, then move or stretch for three minutes. (See our desk routine for help with getting movement while at work).

- Sit on the floor at night in hip positions that you don’t expose yourself to throughout the day.

- Try a standing desk or alternate sitting, standing, squatting, etc.

- The golden rule is that “motion is lotion.” Your best position is your next postion… so stay on the move!

These little additions all have huge impacts on FAI recovery, especially when compounded together. (Here are 57 ways to get more movement throughout your day). Supporting tissue work, stretching, and muscle reactivation with lifestyle changes and posture correction ultimately gives the best results for healing FAI.

How Long Does it Take to Recover from FAI?

A big question is “how long does it take to recover from FAI?” The answer, of course, is it depends.

Depending on how bad your hip mobility is, tissue quality, and overall lifestyle has been, it can take anywhere from just a few months to several years.

Complete recovery is possible, it just may take more time than you anticipated. It also doesn’t mean that you can’t enjoy the process. You may not be where you want to be immediately, but you will feel your hips changing and adapting as time passes, which can be a really enjoyable process.

“But I want to recover fast!”

It is okay to have goals, but instead of obsessing over a hard deadline, do the best that you can and enjoy the improvements as they come.

The most successful clients of ours tend to learn to love learning about their hips/body. They realize they are learning invaluable life skills. Becoming more relaxed about “when they get there” actually helps them get “there” faster!

The Nerdy Science of Hip Impingement

Most people don’t care about anatomy. They have pain and they just want to fix it. But a little functional anatomy knowledge can help you get out of pain and get more flexible even faster.

There is a lot we can discuss here, so we’ll keep the discussion of hip anatomy close to hip impingement.

As we said earlier in this article; the hip is a ball and socket joint. It has the potential for incredible range of motion when trained properly. Here is how it functions:

- Flexion—moving the leg toward the chest

- Extension—moving the leg behind the body

- Abduction—moving the leg away from the body to the side

- Adduction—moving the leg toward the body (toward the other leg)

- External Rotation—rotating the leg so that the foot points outward

- Internal Rotation—rotating the leg so that the foot points inward

These combined functions express the full range of motion of the hips.

Many muscles are involved in these functions of the hip. Here are the muscles broken down by movement category:

Hip Extensors

Gluteal muscles and hamstrings.

The gluteal muscles consist of: the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, obturator externus, obturator internus, piriformis, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, and quadratus femoris.

The gluteus maximus is the strongest of them and the strongest hip extensor. The gluteus medius creates hip stability and internally rotates the femur. The rest of the muscles are external rotators, meaning that they rotate the femur externally.

It’s worth noting that the gluteal muscles do more than this depending on what angle the femur is in relation to the pelvis. You can play around with your hips and legs at different angles to see what muscles fire to create movement in different positions.

The hamstrings consist of three muscles: the semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris. All three extend the hip. The hamstrings also flex the knee.

Hip Flexors

Iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and sartorius. The iliopsoas is made up of two muscles: psoas major and iliacus. This muscle complex is the main hip flexor. The rectus femoris and sartorius are secondary hip flexors.

Hip Abductors

Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia latae. These muscles abduct the hip, meaning they move the hip away from the midline of the body.

Hip Adductors

Adductor brevis, adductor magnus, adductor longus, pectineus, gracilis, and obturator externus. These muscles adduct the hip, meaning they move the hip toward the midline of the body. Some of these muscles are also secondary hip flexors and extensors. The adductors also internally rotate the hip.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Hip Impingement

The most common questions we get about hip impingement are related to osteoarthritis and labral tears.

Hip Impingement and Osteoarthritis

WebMD.com says “Arthritis is a general term that means inflammation of the joints.”

Osteoarthritis, commonly known as wear and tear arthritis, is the most common type of arthritis. It is associated with a breakdown of cartilage in joints and can occur in almost any joint in the body. It commonly occurs in the weight-bearing joints of the hips, knees, and spine.

When x-rays or MRIs show degradation of the hip joint then osteoarthritis can be diagnosed as the cause for hip impingement pain.

Doctors may say that FAI is to blame for getting arthritis. Since FAI can cause your hip joints to collide, doctors blame FAI as a potential cause for arthritis. However, not all those who show signs of hip arthritis feel hip pain.

This article goes into depth in explaining why you don’t need to be afraid of arthritis when dealing with FAI.

Hip Impingement and Labral Tears

The labrum is a ring of cartilage that surrounds the ring of the acetabulum. A labral tear can occur when the hip is impinged. For instance, when the hip is put into flexion or internal rotation and it is impinged, the labrum can be torn. An MRI can expose a labral tear.

Interestingly, like osteoarthritis, not all people who have labral tears experience hip pain. This indicates that labral tears and osteoarthritis do not have a direct relationship with FAI or hip impingement.

While it makes sense that a torn labrum can be painful, it does not mean that the hip can’t work perfectly fine with the right treatment.

If you want to read about labral tears in more detail check out this article.

Summary + Action Steps to Fix Hip Impingement

My name is Shane Dowd and I have hip impingement. In 2011 I was on the verge of surgery for hip impingement. I spent almost all my money ($25,837.29 to be exact) trying to fix it.

This video is how my hips move now:

My partner, Matt Hsu, also suffered with severe hip pain and limitations for years. We both chose to avoid surgery (since it can’t be undone), and we worked on ways to free our hips and get rid of our pain.

We took everything we learned over those years-long struggle and condensed it into a DIY program to help other hip pain sufferers for less than the cost of two physical therapy sessions. If you’re looking for a solution to your hip problems that doesn’t involve drugs, pills, or surgery (and is money-back guaranteed to help you), check out The FAI Fix.

I also put together a handy video and infographic for you, so check those out!

👉 Get our hip mobility routine so you can loosen up your hips whenever and wherever you need to.<