They say, “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.”

While in some cases this pithy saying might be true, when it comes to learning complex skills, it turns out “perfect” practice could be holding you back.

While in some cases this pithy saying might be true, when it comes to learning complex skills, it turns out “perfect” practice could be holding you back.

We’ve been conditioned to think that the path to mastery is paved with finding the “right” routine, using the “optimal” form for exercises, and making sure every rep is spot on. But as I’ve discussed before, ideal form is more about principles and safety than a set of regimented standards.

If you never let yourself mess up, or if you restrict yourself to narrow ways of doing movements, you are actually holding yourself back.

In this article, I’ll talk about the how and why of using research based motor learning strategies in your training to make the path to skill mastery a lot smoother, and a lot more fun.

How Proper Motor Learning Strategies Encourage Skill Development

It seems only logical that, if you want to get good at a particular skill, you have to practice that skill as well as you can, over and over until you get it.

It seems only logical that, if you want to get good at a particular skill, you have to practice that skill as well as you can, over and over until you get it.

In reality, it is more complex than that, as researcher Richard Schmidt demonstrated with his Schema Theory of motor learning.

In this, Schmidt introduced the idea that certain movements and skills are dictated by what he called Generalized Motor Programs (GMP). These are based on the combined inputs the body receives from our movement (sensory information, muscle actions, sensory changes and outcomes of those actions, etc).

Each time you do a repetition of a certain action, your body gathers feedback so it can make that particular sequencing work better next time.

When you practice a cartwheel, for instance, your brain registers:

- the feeling of bending down to place your hands on the ground

- the force with which you kick up your legs

- how you balance while inverted

- how hard you land on the ground at the end of the movement

We take all that information and constantly refine our movement at each practice session.

The problem becomes when people limit and constrain themselves to a quest for “perfect” in their practice. I deliberately use the word constrain because when you provide the same input and stimulus with the same patterns each time, you’ll end up stagnating on a particular skill you’re working on.

Instead, when you allow yourself to make errors and to practice movements in a different way (even if it’s technically “wrong”), you’ll be providing varied and thus higher quality information for your body which improves your learning of skills.

Motor Control is an integral part of Physical Autonomy, so the strategies in this article are an important part of the GMB Method. Let’s take a look at these important strategies.

Five Strategies to Create a Better Motor Learning Environment for Your Body

The biggest challenge with this approach is knowing how to allow yourself to make mistakes, while staying safe and on track toward your goals. The key is using strategies that give you room to make errors, while supporting self-awareness of these errors and the changes that encourage progress.

Strategy #1: Delay Technical Feedback

When training, there is a tendency to want immediate feedback as you’re performing an exercise. If you’re working with a coach, it’s natural to want them to make adjustments to your form as you’re training—that’s what they are there for, right? And when you’re working on your own, you might use a mirror for immediate feedback.

On the surface, this particular feedback of your performance—the technical term is Knowledge of Results (KR)—given during or immediately after a skill would seem to improve skill performance better than delayed KR. This seems logical—of course you’ll do better when you can correct your errors as soon as you make them.

It’s been found, though, that immediate KR improves only short-term performance, whereas delayed KR leads to better long-term retention of the skill.

Why would this be so?

The theory is that immediate feedback interferes with the brain’s information processing of all the sensory and motor pattern reactions during and after the skill performance. The motor learning you would have gotten from “messing up” and giving yourself feedback later on is interrupted by the immediate feedback you’re getting.

In essence, immediate feedback is a crutch upon which you become unknowingly dependent.

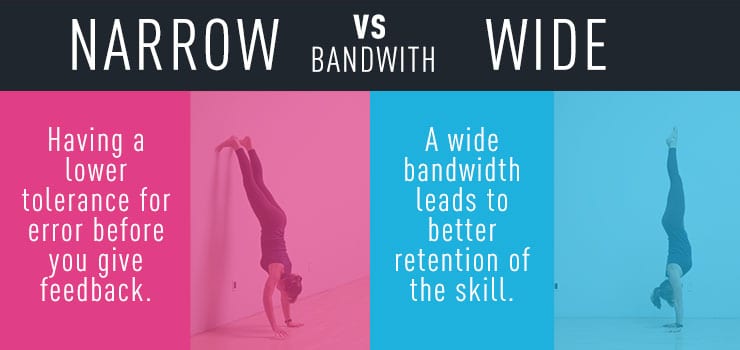

Strategy #2: Give Yourself a Wide Bandwidth

Bandwidth is a concept related to the feedback concept we just discussed. It refers to how much room for error you allow yourself in a skills training session.

If you give yourself a narrow bandwidth, that means you have a lower tolerance for error before you give feedback to correct the error. Much like immediate feedback, a narrow bandwidth means fewer mistakes within the session, and therefore better performance measures immediately following the skill session.

But, just as we saw with delayed feedback, a wide bandwidth leads to better retention of the skill.

With a balancing exercise like the handstand, coming off the wall even just a little bit can be giving yourself a wider bandwidth than relying fully on the wall.

Another good example of narrow vs. wide bandwidth would be when a parent is teaching their kid how to ride a bicycle. They can use a teaching style that gives the kid a very limited bandwidth for error, or they can give them a wider bandwidth.

- Narrow Bandwidth—A narrow bandwidth in this case would be if the bike has training wheels, or the parent is hovering over the kid, making sure they don’t fall off course.

- Wide Bandwidth—The extreme end of the spectrum would be the parent that puts their kid on the bike and says, “Good luck!” with little or no instruction. Something in between would be removing one training wheel from the bike so the kid has some room for error, but not so much that they’ll get hurt. Another option is a Strider Bike, which has no pedals and allows the kid to pedal along the floor with their feet and continually adjust their balancing as they improve. It’s a great form of self-regulating and I personally saw my children benefit from that when they learned to ride their bikes.

In this example you can see that there does need to be a balance between too narrow and too wide of a bandwidth.

When your skill session is too restricted, you aren’t allowing yourself the opportunity to get the maximal motor learning from your work, but you do want to make sure there are some parameters so that you’re staying safe. Give yourself room for healthy error and you’ll improve and retain your skills much more effectively.

Strategy #3: Try an Unpredictable Practice Arrangement

There are different ways to arrange a skills practice session. The most common arrangement is blocked practice, where you repeat the same drill over and over for a particular block of time.

There are different ways to arrange a skills practice session. The most common arrangement is blocked practice, where you repeat the same drill over and over for a particular block of time.

You’d think this approach would be the best path to mastery of the skill you’re practicing, and just as we saw with immediate feedback and narrow bandwidth, the initial measurements with blocked practice show improvement in skill performance.

But this is a temporary boost in performance when compared to a random practice arrangement, measured over the long term, random practice outperforms blocked practice.

Random practice is where, instead of having one skill you drill over and over, you have multiple tasks and varied sequencing in your session.

- Instead of aiming for mastery of a specific skill by practicing it over and over again, we teach diverse skills (with variations of the particular skills themselves) over the course of the program.

- The structure of the course has you doing a different movement every day, which may seem like it wouldn’t lead to skill retention, but because these skills are related, when you return to them at different points in the program, you’ll find you’ve come away with better understanding and performance.

Random practice is likely more effective for long term retention of skills because of the novelty of input to the nervous system. When you do the same drill over and over, let’s face it—it’s boring! Your body keeps going but your brain takes a break from learning.

Strategy #4: Pay Attention to External Cues

Attentional focus refers to the cues you’re concentrating on when you’re practicing a skill.

With internal cues, you’re focused on the internal experience of the movement, whereas with external cues, you’re more aware of the external effects of the movement.

Going back to the example of learning how to ride a bicycle:

- Internal Cueing—In this case, your internal cueing could be contracting your left obliques and pushing your right foot down with your quads, if you feel yourself falling to the right. This is obviously not something a parent would tell their child to do, but adults can tend to overanalyze.

- External Cueing —This could be simply trying to get from one point to another. Start here and get to that side of the park.

While you might think an internal focus would create a better motor learning environment, an external focus is correlated with better skill performance, both short and long term.

Just as in the previous strategies described, an internal focus interferes with motor learning because the information is given too early. An interesting study showed that giving a learner instruction on the optimal movement pattern prior to the performance of a skill led to worse performances in the new movement than providing no instruction at all!

Strategy #5: Break Your Practice into Whole-Part-Whole

A common approach to teaching and learning complex skills is to break the skill down into its simpler components, then drilling those parts of the movement pattern. The separation of a skill into components (no matter how well reasoned) tends to decrease overall performance as compared to practicing the full motor skill.

But breaking down skills is very useful in decreasing frustration and promoting consistency in practice, so it’s not practical to just throw this away. Research should lead us, but not at the expense of interfering with actually doing the work. So, to take advantage of the benefits of both approaches, we use the Whole-Part-Whole method.

With this structure, you’ll go through the full movement pattern, then break it down into components, and finally practice the full movement pattern again.

So, let’s say you’re working on front rolls:

- You’ll start by practicing the front roll as best you can.

- Then you’ll work on the components of the front roll—squatting down low, tucking your chin, coming up onto your toes, etc.

- Finally, you’ll go back to practicing the complete front roll, putting those components together.

This practice structure will help you eke out the maximal motor learning from the skill.

Applying Motor Learning Strategies to Your Skill Practice: The Cartwheel

Let’s use the cartwheel as an example of how we can pull this all together.

First you’ll need a way to learn it, either from an in-person coach or a good tutorial (luckily we have a great one for you!). The tutorial offers you the basics on strengthening and flexibility, as well as progressions to learn the skill itself.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to completely separate a skill from its attributes (strength, flexibility, etc.), but for a clearer illustration we will focus on the development of your skill and performance of the cartwheel and leave strength and flexibility aside. You can see our approach to those attributes required for a cartwheel in our tutorial.

Delayed Feedback

It can be helpful to use a mirror or someone correcting your form in the first session or two, to help alleviate frustration and for safety, if you have concerns. But don’t fall into the trap of requiring immediate feedback to feel better.

Remove that crutch as soon as you can and you’ll improve faster.

Instead, video your practice, then watch the video back after your session is done. You can then use that information for your next session.

Wider Bandwidth

A “correct” cartwheel has your feet and hands starting and ending on the same line of travel.

A “correct” cartwheel has your feet and hands starting and ending on the same line of travel.

Trying to do that with every repetition or else counting it as a “fail” is giving yourself a narrow bandwidth. Giving yourself room for more error, especially in the beginning, is a much better approach.

This wider bandwidth approach gives your body more productive information to adjust and refine as you do more repetitions.

Unpredictable Practice

Here’s where things get a bit more difficult.

The cartwheel is actually a relatively simple skill. You face and move in one direction and the trick to a good performance is keeping your body in that one line and doing it smoothly and gracefully.

There are three variations in the Cartwheel tutorial posted above, but once you get to a certain point you’ll be better off just doing the straight line cartwheel. So it can appear that you are doing the same thing over and over again to an observer.

The random part of the practice is then in your intent and your focus in different repetitions. An example follows with the various External Cues you’d choose to work with.

External Cues

As mentioned earlier External Cues are those outside of your body vs. Internal Cues which are within.

For example, when you throw a baseball you can think about where your elbow is as you throw and how much your hip is rotating. Those are internal cues, whereas thinking of the target of your throw is an external cue.

For the cartwheel there are a variety of external cues to choose from:

- Where are your fingers pointing when you plant your hands?

- Where do your feet land at the end of the cartwheel?

- Where is your gaze directed throughout the movement?

To create a random practice session, you would go back and forth between the different cues.

Whole-Part-Whole

This is probably the most intuitive out of all the strategies. You do the full movement as best you can for a few repetitions, then practice the components, and then finish with the full movement again.

You can break up the cartwheel pretty simply:

- The start, where you are standing and put your hands on the ground. Don’t worry about the rest of it. Just do that and then go back to beginning.

- The middle, where both hands are on the ground. You start in that position and bring your legs up. And you can plop down any way you want, just make sure you do it without hurting yourself.

- And the end, which starts from that middle position with both hands on the ground, but this time you’ll focus on how your feet land.

Create a Motor Learning Environment for Your Skills Training

A dedicated approach that focuses on optimal form and practice is appropriate for building attributes such as strength or flexibility.

But as we’ve seen, when it comes to skill building, you’re much better off setting up an environment for your training that lends itself to maximal motor learning opportunities. The five strategies above can help make that training more effective.

Master Essential Movement Patterns for Any Activity

We designed Elements to incorporate the strategies in this article to develop body control in a wide range of sports, activities, and physical disciplines.