Being injured when you’ve been doing well in your exercise program feels like it throws everything you’ve done off track. Unfortunately, I know that feeling all too well.

You’ve put in the work, steadily improving your skills and strength, and then something goes wrong. Maybe a quick slip led to a sudden injury, or maybe your shoulder just started aching out of the blue.

No matter how it happened, sorting through what’s really going on—and figuring out how to move forward—can be challenging. That’s exactly why we’ve put together this article: to help you understand the root of your injury and give you clearer steps toward getting back to the activities you love.

Contents: What Exactly Happened? / Can I Avoid This? / How Can I Get Back On Track?

Before we dive in, I just want to remind you that the information in this article is no substitute for being seen by a professional in-person if you have ongoing issues–particularly related to pain or weakness.

We’ve helped clients deal with everything from twisted ankles to chronic neuromuscular diseases, and though we don’t give medical advice, we have a lot of experience helping people figure out how to get beyond limitations. Trust us, we’ve seen all the injuries discussed in this article (and more), so we know you can get back to the activities you love.

It’s just a matter of knowing what you’re dealing with, and taking the right steps to get you to where you want to go. This article will give the knowledge you need to get back to doing what’s important to you as soon as possible.

When Should You Seek Medical Help?

You might know exactly what caused your injury, but sometimes that won’t be the case. Either way, the first step to overcoming your injury is to become more familiar with what’s really going on with your body.

You might know exactly what caused your injury, but sometimes that won’t be the case. Either way, the first step to overcoming your injury is to become more familiar with what’s really going on with your body.

But before we get into the most common causes of injuries, it’s important to know when you should seek immediate medical attention from a professional (besides the obvious broken bone or the like). Go see your doctor immediately if you experience any of the following:

- Numbness or tingling in an area that hasn’t subsided within a few days of first noticing it.

- Significant weakness (not related to pain), such as consistently dropping cups of coffee, or a foot dragging when you walk.

- Pain that consistently wakes you up at night.

- Sharp, “shooting” pain that goes down your arms or legs.

- Any pain from trauma (sprained ankle, wrist, fall onto shoulder, etc.) that doesn’t improve significantly within a week or so, and with pain greater than a 5 on a scale of 1-10 (with 10 being most painful).

- Fever, weight loss, or any other vital changes happening for no apparent reason.

Basically, this is all bad stuff. Don’t wait to get things checked out by your physician if you experience any of these symptoms. These could be signs of significant issues and it’s best to go sooner rather than later.

Your Injury Type Explained

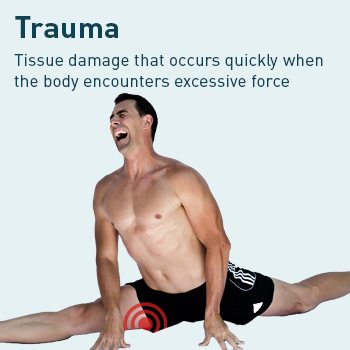

1. Trauma

Trauma is a no-brainer cause of many injuries, and it’d be pretty hard not to know when this happens, as it is characterized by its quick and obvious nature.

Trauma is a no-brainer cause of many injuries, and it’d be pretty hard not to know when this happens, as it is characterized by its quick and obvious nature.

The characteristics of a traumatic injury are:

- It happens quickly

- You’ll usually know relatively quickly how bad the damage is

- The level of injury will correspond with the force of the trauma (in other words, if the damage is worse than it seems like it should be, it’s probably another type of injury)

Examples of this happen all the time in daily and recreational activities. Falls and collisions, tripping and twisting your ankle, and/or your kids jumping on you while you’re on the couch (not that that’s happened to me…)–these are all really common sources of injury.

With trauma, the force must be clearly proportional to the injury, and the extent of the damage is known almost immediately. The amount of swelling, bruising, and pain will indicate how bad off you are, and you’ll usually know right away if you need to go get your injury checked out by your doctor. Of course, if you experience any of the symptoms above within a few days, go see your doctor anyway.

To be even more clear, “I bent over to pick up a sock, and my back went out” is not trauma!

Yes, there seemed to be a specific incident that caused your back pain, but if you bend over to pick up stuff all the time, why did you injure yourself this particular time? A good rule of thumb is if it seems your pain is out of sync with what just happened, it is most likely due to a combination of the complex factors listed below.

2. Overuse

This type of injury is common among “weekend warriors” who (for example) might go all out at a pick-up basketball game on Saturday after not having moved that much in a long time.

This type of injury is common among “weekend warriors” who (for example) might go all out at a pick-up basketball game on Saturday after not having moved that much in a long time.

The characteristics of overuse injuries are:

- Fast breakdown in muscle tissue

- Symptoms occur quickly

- Caused by a change in your environment

Overuse problems are different than a repetitive stress injury (which we’ll talk about next). The difference is that overuse is distinguished by a relatively fast breakdown in tissue, because of the introduction of a stress that the structure is not equipped to tolerate.

The cause is a distinct change in your “environment,” whether that is a new sport or a new pair of shoes. The change can be easily identified and the symptoms appear almost immediately–usually within a few days, and sometimes as soon as a few hours.

A common example is helping someone move out of their house. Unless you’ve been lifting weights regularly (and even if you have been!), I bet you’ll be feeling some tweaks and strains later in the day or the next morning.

Another typical case is adding an extra day of training when your body is just not up for the extra stress.

Perhaps you are getting just enough rest and recuperation on your regular off days from training, and you are not able to tolerate the extra work. If you ignore these symptoms of the “new ache” in your shoulders, or the shin splints that you haven’t had since you ran track in high school, you may be setting yourself up for long term problems.

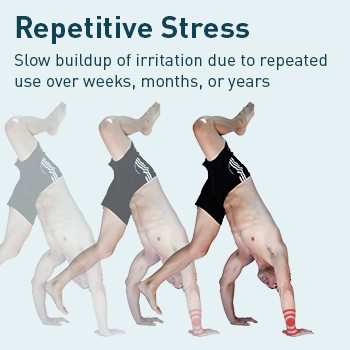

3. Repetitive Stress

This type of injury is often a head scratcher, where you don’t necessarily know the exact cause of the issue. Unlike a traumatic or overuse injury, there wasn’t a specific event that precipitated this injury.

This type of injury is often a head scratcher, where you don’t necessarily know the exact cause of the issue. Unlike a traumatic or overuse injury, there wasn’t a specific event that precipitated this injury.

The characteristics of repetitive stress injuries are:

- Slowly develops over extended period of time

- Buildup of irritation to a tissue

- Pain may be gradual

Repetitive stress injuries are formed by a slow buildup of irritation to a tissue, occurring over the course of weeks, months, and perhaps even years, before symptoms are noticed.

An example is the carpenter who works for years and years without difficulty, yet now notices a lingering pain in his wrist that is worsening. When questioned, he may recall that there was a gradual deterioration in his performance.

Another example from my practice is when I treated a farrier (person who shoes horses) once who had been working for years without trouble but had intense elbow pain for some time before he came in for treatment. But that slow deterioration can be difficult to notice until the pain becomes too much to ignore.

One example from physical training may be that in your sessions you initially feel an ache in your shoulder which comes and goes. But some months later, you notice that pain lingers longer than it has before, is a bit more intense, and perhaps instead of only happening when you exercise, it now appears when you are putting your groceries on a high shelf.

What causes this? Perhaps an illness, or even just the passage of time, which brought strength levels down for a bit while you continued on without any decrease in the volume of your activities.

Unless you’re experiencing any red flag symptoms that require a medical professional’s attention, the strategies we’ll share in chapters two and three will be good for this type of injury.

4. Exhausted Adaptive Potential?

This cause is the most difficult to see, and is likely best assessed by a professional health care provider. It’s a complex issue that can take a keen eye and experience. But it is helpful to know the basic things to look out for.

This cause is the most difficult to see, and is likely best assessed by a professional health care provider. It’s a complex issue that can take a keen eye and experience. But it is helpful to know the basic things to look out for.

The characteristics of an exhausted adaptive potential injury are:

- Most complex cause of damage

- Can be caused by improper healing of a prior trauma, or by the adaptations your body made to compensate for a prior trauma

- The cause is often not the same as the new site of pain

Our bodies’ adaptive potential is defined as the ability to tolerate the various stresses in our daily activities. This is distinct from overuse or repetitive stress, in that the underlying problem is generally not at the area of our pain.

An injury of this kind happens when we’ve had a past trauma that appeared to heal, but in fact, compensated by affecting structures other than the compromised body part.

The true cause (the “culprit”) is often far removed from the site of pain (the “victim”), and the cause of these compensations is what needs to be addressed, rather than just treating the symptoms at the site of pain.

For example, you may have slipped and fallen on some icy ground last winter, and had some pain in your shoulder that got better after a couple of weeks.

This incident may have subtly changed your posture and how you hold your neck. Even though you initially had no pain in your neck, you soon notice a constant neck pain which seems to have appeared “out of nowhere” (this is where the “I bent down to pick up a pen and now I can’t move my neck!” comes in to play).

Weak spots in your physical make-up (such as tight shoulders, trouble bending forward, neck stiffness with rotation to one direction) can create problems elsewhere in your body, and make you more vulnerable to injuries during your training.

Can I Stop Injuries Before They Happen?

When it comes to injury prevention, it’s crucial to face the realities right from the start: there is a potential for injury in nearly everything we do —t he very definition of an accident is that it’s unplanned and unintended. Things will go wrong at some point. You might land a jump at an awkward angle, or simply step off a curb the wrong way and roll your ankle. The question isn’t whether it will happen, but rather what happens when it does:

- How will your body handle it?

- Will you end up injured and facing months of rehab?

- Or will your body roll with the challenge and come out unharmed?

This is where resilience comes in—your body’s ability to adapt to and absorb stress, especially in unfamiliar or unexpected situations. The higher your resilience, the less likely you are to sustain serious damage when things go off track. Pain, swelling, and stiffness aren’t signs of failure; they’re natural signals that guide your responses to these unexpected challenges. By understanding and respecting these signals, you learn to “brush up” against discomfort rather than avoiding it entirely or recklessly pushing through it. This balanced approach can help you recover more quickly when setbacks occur and ultimately reduce the impact of unforeseen mishaps.

In recognizing that not all injuries are the same and not all can be prevented, you shift from a mindset of trying to eliminate all risk to one of preparing for the inevitable. Through mindful practice and incremental adjustments—like reducing range of motion on a challenging move or experimenting with low-intensity variations—you develop the kind of adaptability that lets you navigate obstacles with greater confidence. Embracing these truths about injury prevention sets the stage for training that respects your body’s limits, taps into its natural resilience, and keeps you engaged in the activities you love for the long haul.

Preventing an injury isn’t about living in fear of accidents or constantly playing it safe. It’s about understanding that setbacks—large or small—are an inevitable part of life, and then taking proactive steps to lessen the likelihood and severity of these events.

Prevention means preparing your body and mind to handle the unexpected, rather than simply hoping that bad luck never finds you.

This proactive stance comes down to building a foundation of strength, flexibility, and awareness. Instead of viewing your body as something fragile and easily damaged, think of it as adaptable and dynamic. Through steady, intentional training, you learn to navigate a wider range of movements and scenarios, fortifying yourself against life’s less forgiving moments.

When you frame injury prevention as a journey toward adaptability and resilience, you set yourself up to thrive in unpredictable situations. You stop seeing missteps as catastrophic or inevitable failures, and start viewing them as opportunities to test and refine your capabilities. With the right approach, preventing injury becomes less about avoiding risk and more about cultivating the kind of robust, reliable body that helps you stay active and engaged in the things you love.

How Do I Get Back On Track?

Popular thought on how to manage an injury has shifted over the years. Gone are the days of just icing your injury and resting–and that’s a good thing in our opinion! Movement is the best medicine for the vast majority of injuries.

Popular thought on how to manage an injury has shifted over the years. Gone are the days of just icing your injury and resting–and that’s a good thing in our opinion! Movement is the best medicine for the vast majority of injuries.

There are many different injury management protocols out there, and it seems like there are new acronyms being proposed every day (yup, RICE, POLICE, and MEAT are all acronyms, though I wouldn’t mind eating rice and meat with the band, The Police).

Here’s what they stand for, so you have a frame of reference:

• Rest

• Ice

• Compression

• Elevation

• Protection

• Optimal Loading

• Ice

• Compression

• Elevation

• Movement

• Exercise

• Analgesics

• Treatment

RICE is the old school approach to injury management–just rest, elevate the injured area, ice it, and use compression on the area. While there are certain circumstances that might warrant this approach for short periods of time (I’ll go through these in the next section), I’m not a fan of using this as a long-term solution.

POLICE improves upon the RICE approach by adding in optimal loading, which involves specific movement of the injured area. But the overall approach is still primarily based on rest, with limited movement.

MEAT is the closest approach to how we recommend managing most injuries. Use general movement and specific exercises to get the area moving well. From my 20 plus years of experience as a physical therapist, along with working with tens of thousands of GMB clients, we’ve found that, in most cases, getting moving as quickly as you possibly can will help aid in your recovery.

However, every case is a bit different. Let’s take a look.

When to Rest vs. When to Keep Moving

While a movement-based approach is generally best, some injuries will heal better with more rest, while others will heal better with immediate movement. In Chapter 1, we went through the four most common types of injuries, so let’s see what approach is best for each of those.

While a movement-based approach is generally best, some injuries will heal better with more rest, while others will heal better with immediate movement. In Chapter 1, we went through the four most common types of injuries, so let’s see what approach is best for each of those.

- Traumatic Injury–With trauma, it really depends on the severity of the injury. If it’s bad enough that you have to go see your doctor, you’ll probably need some amount of rest period, but just follow your doctor’s recommendations. If it’s less severe, you’ll likely want to take at least a few days or even a week or two to rest up. This rest period is a good time to get in some gentle movement to keep the blood flowing.

- Overuse Injury–Because overuse injuries are caused by “going hard” when you’re not used to doing so, rest is imperative. But after a few days of rest, once the affected area is feeling mostly better, that’s the time to start making regular, consistent movement a priority. This will protect you from future overuse injuries.

- Repetitive Stress Injury–This type of injury happens over a long period of time, so unless there’s a specific activity that’s aggravating the area, stopping your training is probably not the answer. Instead, adding in some movements and stretches that will help you strengthen and mobilize your area of pain will yield good benefit.

- Exhausted Adaptive Potential Injury–This type of injury can be quite complex and addressing it on your own might not be the best idea, especially before getting your issue checked out. Stop your regular training for now, see a doctor, and follow their recommendations.

As you can see, for most injury types, you’ll do well to keep moving (or get back to moving pretty quickly), rather than resting completely.

When injury strikes, it can feel like everything comes to a standstill. As the text points out, though, not all injuries are created equal. Some are severe enough to require professional intervention—like fractures, nerve-related numbness, or serious ligament tears—while others can be self-managed with mindful movement and gradual reintroduction of activity. The key is recognizing that pain, swelling, and stiffness are your body’s natural responses, warning signals meant to protect you from making things worse.

The first step is to identify what you can still do comfortably. Rather than completely immobilizing yourself at the slightest twinge, experiment with simple, gentle positions and movements that don’t flare up your pain. If your back is locked up, for example, start by lying on your side, or on your back with your legs elevated, to relieve pressure on sensitive tissues. From there, slowly progress to basic drills—like gently drawing your knees toward your chest or performing light leg extensions while sitting—anything that keeps movement tolerable and helps blood flow to the injured area without pushing your pain past a manageable 3 or 4 out of 10.

Consider “brushing up” against your discomfort, rather than avoiding it entirely or bulldozing through it. The goal isn’t to provoke more pain; it’s to gradually recondition your body to trust movement again. Mid-range, low-load activities—such as partial squats instead of full pistols, or brief, low-intensity cycling—can help you build confidence and circulation without risking further damage. Instead of fearing pain, learn to respect it as a guide. Use it to find safe movement patterns, then patiently expand the range and complexity over time.

In short, your path back from injury involves mindful experimentation, steady progression, and the willingness to meet your body where it’s at. Pain is a protective mechanism—treat it as a signal to proceed with care, not a command to halt all activity. With thoughtful adjustments, consistent low-level movement, and a focus on what you can do rather than what you can’t, you’ll encourage healing and set the stage for a return to the activities that matter most to you.

Whether or not you’ve been injured in the past, you want to be confident in your body’s ability to withstand trauma when it occurs—and it will! Trauma doesn’t have to mean getting hit by a car. It can mean something as simple as tripping over a tree branch and landing in a way your body hasn’t been conditioned to handle.

The strategies I’ve discussed will help you make playful movement a part of your practice. Through this work, you’ll condition your body to handle force in positions you’re likely unused to working on in standard gym training. Most conventional exercises don’t leave a lot of room for variation.

Not only will you improve your body’s resilience, you’ll build your foundation for a lifetime of productive training. If you’re looking for something you can easily add into your current routine, check out Resilience:

Specific Training for a More Resilient Body

Our Resilience training program trains your joints and connective tissues to withstand force and impact for confident performance and reduced chances of injury.