Pain is a very complex and emotional subject.

What’s agonizing for one person, may be just a discomfort for another. And those responses can reverse in another situation and context.

It is an unavoidable, and frankly quite necessary aspect of all of our lives. In the simplest terms, pain is a protective measure, your body’s way of signaling danger. For example:

- when you absentmindedly touch a hot pan without oven mitts (you’ll instinctively pull your hand away, avoiding further harm)

- or the sharp pain you feel when you break a bone (you’ll automatically stop moving that area, which would otherwise cause more damage)

These examples illustrate why we actually need pain, but in both instances, the pain is limited and temporary, and hopefully won’t last any longer than required.

When pain is longer lasting, however, that’s when it can affect our daily lives and activities, and can distress us to the point where we’ll try just about anything to simply make it stop.

You can – and many people do – spend years studying all the complexities of pain and how to affect it, but what I’d like to do in this article is give you an overview and introduction to a basic understanding and advice you can use right away to help in dealing with it.

What is Pain? Acute vs. Chronic

We’ve all experienced different types of pain at some point, and we know the difference in feeling between the pain of stubbing a toe vs. a nagging back ache that just won’t go away.

Let’s look quickly at what you need to know about these different types of pain.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is short-lasting, and you’ll usually know exactly what did it.

When we talk of touching hot pans and broken bones, those are examples of acute pain, very quick and immediate sensations along the nerve pathways warning of tissue damage.

Getting hit, falling, and other “insults” to your body can create pain. We all know this. It happens all the time.

In this article I won’t talk too much about acute pain since it most often resolves on its own and simply requires some activity modification. For example, if you feel a twinge in your back while training one day, in most cases, you probably just need some rest to let the area recover.

One interesting thing to note about acute pain, though, is how the central nervous system (which we’ll get into in greater depth below) processes pain in different scenarios.

For instance, if you’re running around on a trail zoned out with your music and the rhythm of your effort, you may brush against a branch, getting a relatively deep cut on your leg, and you may not even notice your injury until you finish.

In another situation, you may be filling out paperwork at your desk, get a shallow paper cut, and feel intense pain immediately.

As we’ll discuss below, pain is a message delivered to you from your central nervous system, and it’s a message that can be altered by dozens of different factors. Depending on the current situation, your personal history, and what other things are happening in your life, you can be more or less sensitive to that message.

Chronic Pain

Something longer lasting, like tennis elbow for instance, will require more investigation.

Here’s where things get very complicated. Chronic pain, defined as pain lasting over 12 weeks, is a construct that is emergent, complex, and without simple solutions.

This is quite clearly seen by the millions of people dealing with a variety of back, neck, and extremity pain, some resolving quickly and some turning into years of problems despite many types of treatment.

The 12-week definition is based on “normal” wound healing processes that include inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation phases, and theoretically by the end of that cycle, pain should end. Unfortunately, this “regular” process of pain resolution isn’t as cut and dry for a lot of us.

It is common for pain to last longer than this course, even when all the x-rays and other scans reveal that the tissue is fully healed. And why it is more than a little frustrating for us to be in pain, even as the doctor declares that we should be all good.

The pain we are experiencing here is a response to a perceived danger. A danger that may have passed, meaning the tissue damage/injury is actually “okay” now, but our nervous system still perceives the issue as unresolved.

Because of this, the rest of this article will be devoted to understanding this phenomenon, and how you can help yourself if you are in this unfortunate situation.

The Nitty Gritty of Chronic Pain

Pain is an interpretation of the totality of inputs to the brain. This consists of many things, including, but not limited to:

- tissue damage

- inflammation and its chemical outputs

- other sensory information, like pressure, sight, heat/cold, etc.

All these various inputs, and their complex interrelationships with the context and nervous system interpretation, explain why the pain response is so variable.

So here starts the confusing dilemma of separating tissue damage from sensitivity and all of the many and varied factors that can influence the perception of pain and suffering. Stress, anxiety, life situations, your past history, and other circumstances all come together in determining how pain waxes and wanes beyond your body tissue’s actual “physical” status.

The latest science reveals that there can be little correlation between tissue damage and the perceived pain.

You can take two MRI scans of different people that show similar structural problems, and one will report no pain while the other can barely move without wincing. When you consider all the inputs that go into creating a pain sensation, it’s clear that it’s not as simple as tissue damage = pain.

It’s a lot more complicated than that.

“Emotional Component” does not Equal “It’s all in your head”

One important type of input that many people don’t think about – or even discount – is psycho-social input such as stress, anxiety, depression, and belief that you can (or can’t) get better.

One important type of input that many people don’t think about – or even discount – is psycho-social input such as stress, anxiety, depression, and belief that you can (or can’t) get better.

The stress and emotional components of suffering don’t at all imply that the pain is “in your head” or that your pain is not “real.” It’s an assertion that pain can increase or decrease based on the totality of what is happening in your life, and based on what other inputs are affecting your nervous system.

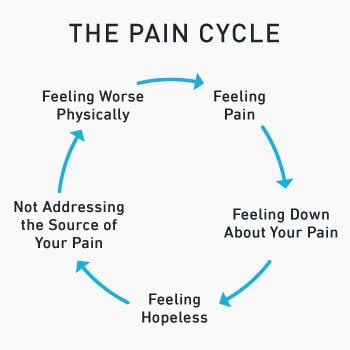

Recognizing this is an important part of addressing your condition, as it can often create a cycle that is difficult to deal with and break.

The term “pain and suffering” is instructive because they really are distinct entities. Suffering relates to how you deal with the presence of pain in your life and this specific reaction should be addressed as much as any physical treatments.

Methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness based stress reduction (MBST), are important complements to a physical treatment protocol.

Treating Chronic Pain

As you can see from all the complexity of chronic pain described above, it’s quite impossible to make sweeping recommendations here for treatments that work for everyone. There’s no such thing.

When people ask us if any of our programs or articles here are appropriate for a client’s conditions or if they will help them overcome pain, this is a very difficult thing to answer. It all depends on so many factors happening with you or the person you are trying to help.

Of course we want to help and it’s no better to just throw in the towel and give up, but it is also more appropriate to emphasize improving function and capacity vs. assuming something will relieve someone’s pain.

I make educated decisions with my patients and these yield good results (based on prior clients’ successes and their reactions to treatment). But it would be not only disingenuous but deceitful to say a particular and specific approach is the solution for all ills.

The intricacy of pain and our personal variabilities require an approach that is flexible and adaptable to our individual situations to break through the problem.

Science is a Guide

Scientific research works incredibly well in evaluating a particular therapy or modality against chosen variables, especially in comparison to another type of treatment, or simply doing nothing at all. It cannot be stressed enough how important good science is in our understanding of how our bodies work and how they react to interventions.

We’ve got good science telling us exercise works well for pain from specific conditions. Don’t ignore this research.

If there is a intervention that we can be nearly 100 percent sure will help, it’s exercise. For example:

- Low Back Pain – We have good data showing that exercise (of almost any kind) has a positive impact on low back pain.

- Achilles Tendinopathy – Research supports the use of eccentric and concentric exercise for relieving pain from achilles tendinopathy.

And of course the trick is in the proper application of exercise in appropriate dosing of intensity, frequency, and volume for each individual.

There are also many studies which show various concoctions (homeopathy, herbals, etc.) and treatments (“energy work”, ultrasound, etc.) have no benefit. That being said, I feel it is unhelpful to tell someone that whatever intervention they have used to help them with their pain is not “real” even if the particular mechanisms and reasonings behind the treatment are scientifically dubious.

When a patient tells me this cream or this herb or whatever really helped them, and I know that the research may say otherwise, I have never told them “what you are feeling is WRONG!” How can that be helpful?

Disregarding someone’s personal experience is a great way to distance yourself, and frankly, make you look like a jerk.

Placebo and Nocebo

The placebo effect doesn’t mean you’re getting the wool pulled over your eyes. It’s a complex mechanism that can actually be effective, unlike the nocebo effect.

You’ve likely heard of the placebo effect, wherein an intervention that should induce no physiological change (the sugar pill is a very common illustration) creates a change.

It’s very easy to simply dismiss this as a mere psychological effect and call a sugar pill or sham treatment “fake”, but it is in fact a very complicated process. It involves environment, patient and practitioner expectations, prior history, emotional effects, and many other factors.

It is very real and also at times very helpful.

Just as our variable emotional response to pain does not make the intensity less real, when someone experiences a positive result from a therapy, even if it may be due to the placebo effect, that does not mean the benefit is less authentic.

To dismiss positive benefit as “not real” is wrong and most thoughtful clinicians will say nothing of the sort.

Along with placebo, there is its opposite, the nocebo, which is the introduction of something which should create no biological effect yet, intended or not, causes an adverse response.

And this is what I see happening with the various debunkings and skepticisms of certain treatments. Of course, I am not rejecting science, it is equally wrong to say, “well then everything works sometimes for some people.”

And I am absolutely not saying that we shouldn’t expose poor practices and treatments that are shown to be harmful or worthless.

What I am saying is that there is a difference between uncovering dangerous methods and being so cynical that what people are hearing is “don’t try anything else but these few things we know about for certain.” This can be as much of a nocebo as telling someone there is nothing at all they can do for their pain and they just have to live with it.

Being so antagonistic about styles of treatment can make a person think that, “well, it seems nothing really works.”

Again, I would never espouse something that is known to be harmful, but the interplay between physical and psychological aspects of pain relief is incredibly elaborate and no one can truly have the “one answer.”

I favor a more pragmatic than dogmatic approach to it all.

You Won’t Know Until You Try

When I work with patients I also sometimes have to try different things out before finding the right “fit” for that patient. That’s how finding answers works.

It may seem too simple a concept, especially when we’d all like to know if something will be exactly what we need before we start, but the reality is you won’t truly know if something works for you until you try it.

This is the essence of science.

You give yourself a trial of an intervention over a reasonable amount of time and then measure the results and evaluate how to proceed – that’s about as scientific as it gets.

I tell my patients and clients to give me 2 weeks, with my standard line being, “in that time you should know if what we are doing is helpful, probably not to 100% better but enough to know that this is the right track for you (or not).” And if in that that time there is progress (that is meaningful to the individual), then that’s a good sign to continue on.

Using the Central Nervous System to Your Advantage

As we’ve discussed, the nervous system is an amazing and convoluted structure that’s responsible for how we interact with everything around us. We can actually use this interplay to our advantage.

We know that when chronic pain is present, it affects the nervous system in myriad ways. For instance, those with chronic pain experience:

- Decreased Two-Point Discrimination – This is a skin sensation test that measures a person’s ability to discern whether there are two distinct points touching the skin vs. one point. When a person is in chronic pain, they have a lessened ability to distinguish this accurately.

- Impaired Proprioception – This is the awareness of the relative position of your body in space, which is important for movement, balance, and coordination. Those suffering from chronic pain often have decreased proprioception as well.

- Sensitization – This is an astonishingly complex topic that fills entire courses and textbooks, of which two of the most readable and entertaining researchers are Lorimer Mosely and David Butler. Rather than adding another dozen pages to this post trying to work through this deep subject, we can simply state that sensitization means that pain begets more pain. In long standing pain issues, the body/brain is made more sensitive to recurrences based on sensory inputs that might otherwise be ignored if there wasn’t a previous pain response. Pain becomes like a particularly bad habit, frustratingly hard to get rid of.

With these concepts in mind, we can begin to understand how to use these to break free from the pain cycle.

If your body sensations and proprioception are affected by pain, it stands to reason that working on body awareness and proprioception can affect your pain. Spend time on a variety of movements that provide different stimuli and influences on your body sensations and you’ll induce changes in pain perception.

Likewise with sensitization. If pain begets pain, you need to “convince” your body to lose its memory of pain.

There is a great post by Todd Hargrove on sending “good news” to your brain about how your body is doing, and he argues that you should seek to do this in every training session.

After an injury, there is invariably a period of very limited movement. In this case, even the simplest rehab exercises can have such a profound impact on acute pain. I’ve seen people come into the clinic barely able to move and with some gentle handling and exercise, they walk out feeling significantly better.

And the same can happen with more chronic issues.

The more you can replace poor memories of painful experiences with new memories of the “good news” as Todd calls it, the better. Part of this is doing what feels “good” and avoiding what feels “bad.”

Some years ago there was a big push for classifications of conditions to better affect treatment, and out of this came the concepts of flexion (forward bending) or extension (backward bending) intolerance. So that instead of specific diagnoses we now look at situational factors that can aggravate your issues.

Activities such as being slumped at the steering wheel or at the computer provoke back problems in some, while standing for long periods and reaching up bother others. It’s a very apparent and simple thing but recognizing exacerbating activities and limiting their duration and frequency helps quite a bit in managing symptoms.

My Own Experiences Dealing With Pain

In addition to my experience as a physical therapist treating patients in pain, I’ve also been “on the other side of pain” so to speak.

I’ve had mid and low back pain since I was a teenager, and as my young co-workers remind me quite often, I’m old now. Thankfully it’s managed well with exercise and understanding of the primary aggravating situations.

I’ve had a lot of different treatment interventions over the years, from rolfing to spinal manipulation, and osteopathic technique to dry needles.

And while I had very good benefit, especially in the acute periods following an exacerbation, the treatments didn’t “cure” my condition, but rather allowed me a window of opportunity where the pain was reduced enough to get back to the flexibility, strength, and motor control exercises that mitigate the pain.

- Improving motor control can help pain conditions for the reasons we’ve talked about above, with the practice of bettering sensation discrimination and body awareness.

- Working on your flexibility can help, not necessarily because of structural changes, but more likely because of improving your ease of motion and replacing the memories of pain and stiffness with amended experiences.

- And when we talk about strengthening for pain control, it’s not because you are building up an “armor” as a protection from insult, but more often it is for the sensation of stability, to keep all the sensitized structures feeling secure and stable.

If I were forced to summarize the best approach to pain management in one sentence it would be as follows:

Improving your body awareness and tolerance in different movements and modifying your habits as needed, especially those that generate pain, is the key to long lasting change.

You CAN Overcome Your Pain

I’ve had the opportunity to treat many patients over the years, and have many examples of when this approach has worked.

- One patient came to me with low back pain that had been going on for years. After one treatment with me, she told me she had immediate pain relief that lasted several days.

- Another patient had daily headaches for 20 years. After one session and teaching her one specific exercise, she’s had lasting relief from her headaches.

I don’t share these to boast of my “magic” techniques, but instead as an illustration of how pain cannot be simply related to tissue damage or structural issues. Otherwise, how could they be affected by one session after years of trouble? It isn’t that simple at all.

There was some very complex interplay between our expectations, education, and physical intervention, and the particular patient/therapist interdynamics that led to the result.

And I would be lying if I said I knew exactly what. Be wary of anyone that says they for know for sure.

The best ways to decrease and prevent pain issues are to work on them gently and progressively, increasing your strength and flexibility in all motions, by exploring your active movement in new and creative ways, and understanding that pain doesn’t necessarily mean damage from one causative factor.

Pain is a complicated issue and anybody selling you the “one secret way” to deal with it is either deluded or predatory.

Address the underlying issues that are responsible for many pain conditions, so you can stabilize your body, move with ease, and use the relationship between pain and the nervous system to your advantage.

Improve Your Condition

Build strength, flexibility, and control through locomotive exercises and targeted mobility work, so you can move the way you want to for a lifetime.