The Bridge, also called “wheel” in yoga, is a staple gymnastics position which demonstrates great flexibility in your shoulders, spine, and hips, as well as shoulder and upper back strength.

It also can seem impossible to do if you have trouble just reaching behind you to grab something from the back seat of your car!

And the truth is the vast majority of people really don’t NEED to do a bridge. But it’s also true is that all of us would benefit significantly from more strength and suppleness in our shoulders, spine, and hips. And that’s what happens when you practice and train to perform the bridge.

The bridge itself isn’t necessarily the goal, it’s the training for the essential components of it. You’ll very quickly be alerted to your own particular strengths and challenges. And this is very valuable knowledge!

The most common challenges and sticking points in achieving the bridge are:

- Shoulder flexion flexibility and strength

- Upper Back extension mobility

- Hip Flexor flexibility

- Quadriceps flexibility and strength

Wouldn’t it be great to improve in all of those things? That’s what will happen when you are consistent with the exercises we’ll show you here.

Bridge Tutorial Video

I’ll share more details for each of these exercises below.

But first, I need to warn you that bridging isn’t for everybody. It may be inappropriate for your physical capabilities, or it might just not be worth the effort with regard to your training goals.

Let’s look at who should and should not practice bridging…

Why You Shouldn’t Practice the Bridge

We’ve said that a fair amount of people don’t necessarily need to work towards the bridge, but are there people who really SHOULDN’T do one?

If any of these sound familiar, you should avoid bridging:

- Current shoulder pain/weakness that precludes full flexion (impingement, tendonitis).

- Current neck and back pain/weakness which limits back bending.

- Current elbow pain and weakness which limits extension.

Don’t get discouraged though; you don’t need to avoid all irritating movements forever.

You don’t need to be this flexible, but the idea of bending this way shouldn’t *hurt*

Don’t ignore your pain and symptoms, but also don’t think you should do nothing but rest.

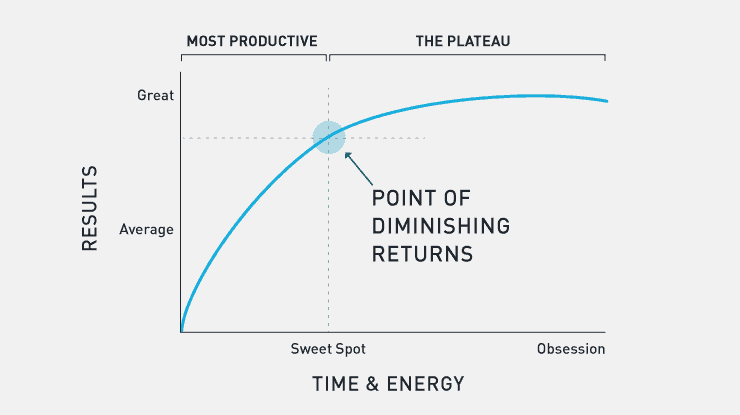

Your pain and body won’t change if you keep aggravating your condition, but it also won’t change if you do nothing at all. You can find the sweet spot of activity that will change your body, and we can help you do that.

The Cost/Benefit Ratio of Bridge Training

No matter your condition/injury history though, you can absolutely progress if you want, but it’s up to you to decide if it’s worth the time/effort/energy. Especially relative to everything else you’d like to do.

Is the amount of time you’ll need to improve your bridge worth the time that could be spent doing other things?

In economics, there’s a term called “opportunity costs”, the cost of what you’d lose when you choose one option over the other. This applies to every choice we make, sometimes it equals out, and sometimes there’s a significant difference.

It’s not a right or wrong thing, you’d just have to decide what value you place on achieving a bridge.

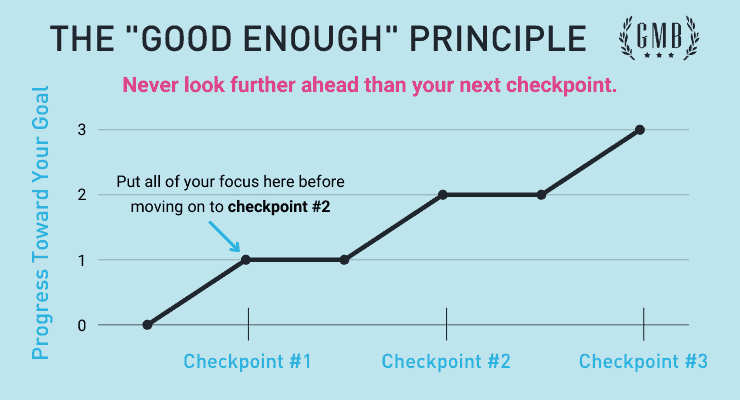

Good Enough (is good enough, I promise)

If you decide that bridging isn’t for you, that’s not saying you should give up on life.

Social media rewards extreme opinions and outsized reactions to fuel the engagement algorithm. As a result, you don’t hear a lot of nuance – more frequently, it’s an all-or-nothing:

- “Go hard or go home!” (Yet research shows that 60-70% effort is more than adequate for making fitness gains)

- “Never settle for mediocrity!” (Yet everyone is mediocre at most things – that’s literally what it means to be average)

- “Optimize everything!” (Yet consistency in a “suboptimal” program will quickly overtake an optimal one you don’t do)

My point is that it’s not an admission of weakness or failure to decide you don’t need to train bridging.

In fact, we don’t include bridges in any of our current GMB programs. Does that mean we’re “settling for mediocrity” or “giving up” on our potential?

No. It means that, having taught many, many thousands of people, we’ve seen that most people don’t actually need to be able to perform a full bridge.

Unless your sport/activity requires you to have that full bridge, you’ll get the vast majority of health benefits from spending just a reasonable amount of effort and time on the bridge preparatory exercises shown here. Stronger and more mobile shoulders, hips and spine can be had in a relatively short time with relatively short efforts.

It’s also useful to know that you can spend less time on your strengths and more time on what’s more difficult to maximize your training efficiency.

What to Do Instead of the Bridge

Maybe I’ve convinced you that a bridge isn’t fully necessary, but you still want the benefits…

Well, you’re in luck, because there’s a lot of things you can do to increase your back flexibility. shoulder range of motion, hip mobility, and joint strength. In fact, unless you’re completely new to GMB, you know that our programs (and this website) are full of exercises that train those attributes.

Most people can get the primary benefits of bridge training by practicing the other backbend exercises shown in the video above and explained in more detail below.

So with that said, for whom is a bridge a necessity?

Who needs to do a bridge?

Gymnasts might be the first ones to come to mind. The bridge is literally a skill that is part of the requirements of the sport. And for performing arts athletes – think dancers and acrobats – being able to bridge is part of a lot of choreography. This is how Ryan learned to bridge growing up competing in gymnastics.

It’s practiced a bit differently in yoga – and even differently depending on what type of yoga- because of different intentions and traditions.

I spent a good amount of time and energy learning the wheel pose when I was practicing yoga seriously. I’m very grateful for what I learned in Ashtanga yoga from Cathy Louise Broda in Honolulu nearly 20 years ago. Something about 6 am daily practice sticks with you! It helped me to understand a lot regarding specific practice and our capabilities.

I spent a good amount of time and energy learning the wheel pose when I was practicing yoga seriously. I’m very grateful for what I learned in Ashtanga yoga from Cathy Louise Broda in Honolulu nearly 20 years ago. Something about 6 am daily practice sticks with you! It helped me to understand a lot regarding specific practice and our capabilities.

Ryan isn’t a gymnast anymore (and he was also a certified yoga teacher), and neither of us practice yoga specifically any longer. So if you notice any “discrepancies” in what we teach here vs what you, or your teacher, espouses we’re not going to debate you. What you’re doing is what you should do. We’re teaching it emphasizing the aspects that we’ve found has helped people over the last couple of decades of teaching.

Also, as martial artists, we both find bridging and the prep movements extremely valuable. In particular, grappling martial artists and wrestlers for their ability to defend and reverse positions.

The bridge is a component of doing all of the above activities skillfully and at a high level of performance, either on its own or as part of a bigger skill/technique. Aspects of the bridge; the fundamental spine and shoulder mobility, shoulder strength, and balance/spatial awareness are a big part of doing well in these sports.

Who else?

Well you if it’s something you’re interested in!

If it’s something you’ve simply just wanted to be able to do, then you should absolutely go for it. If you already are capable or close to fully doing it, just a bit of focused time on what we show here will have you “own” the movement and cement it into your movement capabilities.

If you are further away from it though, that’s when you have to do some introspection. Examine what is really motivating you and how to appropriately use your time and energy.

When you decide on getting and remaining fit, you have to navigate around what’s best for you with respect to prior injuries or just too many years of stiffness under your belt.

Exercises and Key Points for Bridge Training

The following exercises can help you get a bridge by opening up and strengthening your shoulders, hips, and spine.

You can also focus on any of these as a worthy exercise in their own right. Even if you don’t do a full bridge, you can make a lot of progress working on the following movements.

Upper Thoracic Extension

You can get away with having less backbend in your upper back if you have very flexible shoulders, and also use more of your low back, but this can cause issues by placing undue strain on those smaller joints. When you can distribute forces through a larger are, you’ll have much more margin for error and have a greater capacity for load and movement options.

You can get away with having less backbend in your upper back if you have very flexible shoulders, and also use more of your low back, but this can cause issues by placing undue strain on those smaller joints. When you can distribute forces through a larger are, you’ll have much more margin for error and have a greater capacity for load and movement options.

Key Points:

- Focus on opening through your chest

- Breathe in as you stretch to expand your ribs as well

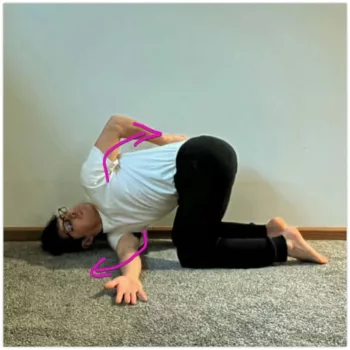

Quadruped Thoracic Rotation

In the spine, rotation is coupled with flexion and extension. Rotation to one side is extension on that side, and flexion on the other side. In other words, forward and backward bending improves when you work on rotation.

In the spine, rotation is coupled with flexion and extension. Rotation to one side is extension on that side, and flexion on the other side. In other words, forward and backward bending improves when you work on rotation.

Actively moving through rotation also improves your muscular control into these positions, which a lot of us sorely need.

Key Points:

- Focus on moving the shoulder as far as you can

- Press into the ground firmly for stability

Kneeling Backbend

In this motion we aren’t fighting against gravity, it in fact will assist us into more backbend which can help us relax into the movement. This can give us a better sense of how it is to be in the bridge position.

In this motion we aren’t fighting against gravity, it in fact will assist us into more backbend which can help us relax into the movement. This can give us a better sense of how it is to be in the bridge position.

Key Points:

- Relax your glutes

- Lift your chest up and away from your hands

Lunge Twist

This is a combination of lengthening your hip flexors as well as rotating your spine. In this position there will be an automatic “locking” of your low back so the stretch forces will be more on your midback and hips.

This is a combination of lengthening your hip flexors as well as rotating your spine. In this position there will be an automatic “locking” of your low back so the stretch forces will be more on your midback and hips.

Key Points:

- Tuck your hips under you (posterior pelvic tilt)

- Keep tall and lead the rotation with your shoulders

Camel Stretch

This classic stretch moves on from the foundation of the previous kneeling backbend. The intentions and motions are the same, just amplified by your shoulder and arm positioning.

This classic stretch moves on from the foundation of the previous kneeling backbend. The intentions and motions are the same, just amplified by your shoulder and arm positioning.

Key Points:

- Push your hips forward

- Press down through your hands to help lift your chest

Quad stretch (Kneeling)

One of your hip flexors (rectus femoris) also crosses the knee. So to fully put this muscle on stretch your knee should be bent. Be as stable as you can through your hands/elbows to control the movement at the best level for you. Also be aware of the arch in your low back. There will naturally be some arch but watch for overdoing it. Not only can this be too much of a strain, it will also take the stretch away from your legs, which is where you want it to go.

One of your hip flexors (rectus femoris) also crosses the knee. So to fully put this muscle on stretch your knee should be bent. Be as stable as you can through your hands/elbows to control the movement at the best level for you. Also be aware of the arch in your low back. There will naturally be some arch but watch for overdoing it. Not only can this be too much of a strain, it will also take the stretch away from your legs, which is where you want it to go.

Key Points:

- Brace well in your stomach and flatten your lower back

- Think of being “long” from your knees to your head

Shoulder Bridge

By taking away the use of your arms, this bridge version allows you to focus more on your upper back bending and properly pushing through your feet to lift up. If your neck bothers you in this position, you can roll up a towel or mat and place under your shoulders.

By taking away the use of your arms, this bridge version allows you to focus more on your upper back bending and properly pushing through your feet to lift up. If your neck bothers you in this position, you can roll up a towel or mat and place under your shoulders.

Key Points:

- Roll your shoulders together so you feel stable lying on them

- Lift your hips by pushing through your heels

Head Bridge

In this version of the bridge, you’ll extend your focus to include arm positioning. Though your head is on the ground, it should not be bearing all of your upper body weight, the majority of weight should be through your feet and hands.

In this version of the bridge, you’ll extend your focus to include arm positioning. Though your head is on the ground, it should not be bearing all of your upper body weight, the majority of weight should be through your feet and hands.

Key Point:

- Push through your hands firmly for stability

Low Bridge

Next is lifting up so your head is off the ground. With your arms bent you’ll be working on your arm and shoulder strength as well as the mobility of your back and shoulders.

Next is lifting up so your head is off the ground. With your arms bent you’ll be working on your arm and shoulder strength as well as the mobility of your back and shoulders.

Key Points:

- Experiment with your weight distribution

- Shift back and forth between more weight through your feet or your hands

Full Bridge

Now you’ll put all the concepts and explorations you’ve done all together!

Now you’ll put all the concepts and explorations you’ve done all together!

Pay attention to:

- The pressure through your hands and feet

- Using your leg drive to lift up instead of your glutes

- Opening your chest and rolling your shoulders back

Bridge & Spinal Mobility Movements from GMB Programs

If you’re looking at all this and thinking “How do I integrate all these different moves and progressions into my routine,” you’ll be glad to hear that we’ve already done the hard part for you.

Even though we don’t explicitly train bridging in our current programs, we train the qualities required to do a bridge.

Elements addresses most of what you probably want out of bridge work.

- Bear – shoulder and thoracic extension

- Crab – chest and hip extension

- Bear to crab to bear combinations

- 3-Point Bridge (this is a great end goal for most people)

Bridge-Related Movements in Sequences:

- Arm extension swipe

Bridge-Related Movements in Mobility:

- Seated twist

- Quadruped twist

- Cobra

- Camel

So you can see that hip opening, shoulder mobility, and spinal extension (among others) are more than adequately addressed in the GMB Curriculum 🙂

And if you’re doing another program that includes similar movements, you also may not need specific work toward a full bridge. Remember: the goal isn’t gymnastics or yoga; the goal is a strong, healthy body that can move with power and ease.

Common Bridging Mistakes

I could probably fill a whole article just with details of poor technique and training protocols I’ve seen, but YouTube is already filled with “19 Bridge Mistakes (don’t EVER do #8)” videos, so…

I could probably fill a whole article just with details of poor technique and training protocols I’ve seen, but YouTube is already filled with “19 Bridge Mistakes (don’t EVER do #8)” videos, so…

Here’s a few general cautions with regard to how you think about bridge training:

Don’t just dive into a full bridge right away as your main training. You should continually re-assess your limiting factors and spend the bulk of the training on those while also practicing the bridge.

The converse is to only do variations and never trying the bridge because you “aren’t good enough yet.”

Skill and training is specific and you have to spend some time actually trying to perform a movement. As long as it’s safe and not too painful you should try it. Uncomfortable is fine. But you’ll learn a lot by trying even if you can’t fully perform it.

Another big mistake is not exploring movements to control your motion into and out of the bridge.

Don’t think that your goal is just to slam up into the bridge and stay there. Comfort and capacity in the bridge involves being able to move freely in and out of position with control and ease

Again, there’s a thousand “wrong” ways you can do a bridge, and some of them really depend on your goals. If you talk to a gymnast or a yoga instructor, you might some very opinionated answers (that may or may not have anything at all to do with what will actually work best for you).

You have to decide what’s important for you, and I hope this article has helped put bridging into better perspective for you.

To Bridge or Not to Bridge… You Still Need a Strong, Flexible Back

As I mentioned at the start, you may not need to do the full bridge at all, but as you go through all of the movements we’ve shown here you’ll realize just how much benefit you’ll get from choosing to be consistent with the exercises leading up to the bridge.

For a complete training plan that contributes to the shoulder, spine, and hip strength and flexibility that will help your bridge, our programs will take you step by step through all you need to know and practice.