Let’s say you have three major training goals:

1️⃣ build some back strength

2️⃣ finally learn to do a cartwheel

3️⃣ loosen up those hamstrings

(or insert your goals here)

You don’t have tons of training time, so pursuing all three at once incorrectly can leave you with little progress to show for it.

You don’t have tons of training time, so pursuing all three at once incorrectly can leave you with little progress to show for it.

How can you train effectively for several different goals?

You can achieve multiple training goals but it requires thoughtful planning and execution, both in the program you are following currently and where it fits in to the rest of your training year.

Periodization is the technical term for a method developed in Russian sports training and exported over to the U.S. and other countries. It has specific connotations and details but at its core it is the intelligent and thoughtful cycling of different training regimens according to your needs and capabilities.

Through cycling your training, you’ll hold on to the gains you’ve made in previous cycle emphases, as you shift over to other priorities.

Here’s what you can expect in this article:

- We’ll help you understand how cycling works

- You’ll learn how this approach will help you break through plateaus and get better faster

- We’ll show you this concept in action so that you can create your own plan around your particular goals

You can achieve many different goals but working on them all at once will only hinder your progress. You don’t have to do it all to have it all.

What is Periodization, or Goal Cycling?

With this approach you’ll spend dedicated time on one attribute then put it on hold as you move on to the next attribute.

Periodization simply means focusing your training on one specific skill, attribute, or program for a chosen period of time, then transitioning to another attribute or program in a planned and progressive schedule.

This enables you to make good progress on each goal, one after the other. And the really clever part comes at the end of a particular schedule.

That’s when you can cycle back and work on the first goal again.

Cycling back through training periods does two great things:

- it makes sure you don’t lose your earlier gains.

- it actually your progress toward each goal because you have new skills and attributes from the other complementary periods.

In general there are two main types of periodization. We’ll explain both of them and show you how they are used in our programs, as well as how you can use these concepts for your training.

Linear Block Periodization

Our apparatus programs (including Rings One) follow a linear periodization model.

We all know there are distinct attributes in physical performance. Strength, endurance, power, skill — these are all distinct (but related) entities.

In this classic scheme of periodization, you’ll take the attributes you want to build and break them into training “blocks”. A block can be any period of time, really, but the traditional linear approach generally breaks these into 4-6 week blocks.

So, for example, you could spend 4-6 weeks on general conditioning, then the next 4-6 weeks on strength, then finish off with a shorter block where you lessen your training volume a bit and focus on a more specific end goal.

We use an approach similar to this in our Level One apparatus programs (Rings One, Parallettes One, and Floor One).

We use four training blocks in these programs (4-5 weeks on strength, then 4-5 weeks on skill building, then 2-3 weeks on combination movements, and finally 2-3 weeks on combining everything from the previous phases into a skills flow).

This approach works well for building up to a specific goal, as in these apparatus programs, building towards performing the final flow routine with high quality and ease.

It’s similar to the approach used in athletics, where the athlete might be on a year long cycle, working up to a championship. Or the cycle could be even longer, such as the four year cycle used for the Olympics. Regardless of the length of the cycle, these blocks build off of each other and get you closer to your ultimate goal.

Non-Linear Periodization

Our Integral Strength program is an example of non-linear periodization.

Here’s where shorter blocks come into play. With this approach, you can work on different attributes on different days in the same week, so a “block” would be just one day.

With this approach, you might work on strength on one day, power on the next, and endurance on another.

An example of this approach is in our Integral Strength program. The overall goal of increasing strength is achieved by cycling through workouts focused on power, endurance, and conditioning. Over the course of eight weeks those short blocks add up to creating a comprehensively strong body.

This is different from, say, the classic bodybuilding approach of working on specific body parts on separate days. Instead, you’re training different attributes on different days.

Even though you’re training these different attributes within the same program, you’re never focusing on more than one on any particular day. This gives you the chance to get as much out of that session as possible, and not have your attention split between different goals.

You Don’t Have to Do it All: How You Can Reach Your Goals Faster With Smart Planning

As we’ve touched on already, periodization was first put into practice for professional athletes working up to an event or competition.

The Russian sports scientists who developed this theory saw that, by cycling through different blocks, these athletes were able to peak at just the right time (for the competition), and not too early or too late.

The good news is even if you’re not a professional athlete (and I’m guessing you’re not), you can use these same principles to reach your goals in a smarter way.

It’s not the specific and complex schemes of a year long sports periodization plan, but the overarching concept of smart and thoughtful cycling of priorities, that will give you consistent lifelong progress.

And it’s why they’ve been built in to the GMB Method of training since the beginning.

Proper Cycling Gives You Ownership of Your Training

With the way most people train skills or work toward their training goals, it’s no wonder the idea of focusing in on one attribute and putting others on hold would create some anxiety about “losing gains.”

Yet what happens when your attention is split and you’re working on 5 or 6 different things at once is, you don’t truly own any one of those things.

You simply won’t have the solid retention you’d gain with the unrelenting practice in a well planned cycle.

When you focus your efforts on one thing for a while, by the end of that training block, you’ll own it. That doesn’t mean you’ll have reached perfection. It just means that you’ve given your body the chance to say, “I’ve got this.”

The work you’ve put in will stay with you, and it won’t take much effort to get it back to the prior peak and climb past it when you come back around in the next training cycle.

With a good plan, you keep most of the gains you made in earlier training periods, and when you come back to that goal, the skills and abilities you built in the intervening periods enhance your progress.

As you can see in this graph, when your programming is set up properly, as you cycle through one attribute, it will peak and maintain for quite a while as you work through the next attribute. Yeah, that first attribute might get a little rusty while you focus on others. But you won’t lose it.

And you’ll have gained ownership of so much more than in a haphazard training style.

Combining all those attributes over time will get you to your goal without the frustration that often comes along with the “trying to do it all” approach.

How to Make Your Own Plan

Okay, now that you’ve got a good understanding of how much better proper planning is, and how it works to help you make improvements and reach your goals, it’s time to put it into action.

To help you figure out the best plan for you:

- We’ll start by discussing how to identify your goals

- Then we’ll talk about how to assess your needs so that you can order and prioritize your training blocks.

- Finally, we’ll go over the biggest challenge people face with this approach (and how to work around that)

Identifying Your Goals

Getting stronger is a good goal, but think about your motivations so you can be more specific in your goal setting.

Before creating your plan, the first and most important step is figuring out what your goals actually are.

That may sound simple, and you may already have a running list in your head. But for many people, it’s actually pretty difficult to come up with clearly defined goals.

Sure, you might have some general goals in mind – getting stronger, losing weight, becoming a better runner – but when you think about it, those general goals don’t tell you much about what’s important to you and why.

- Why do you want to get stronger? Who or what is driving you toward that goal? And what markers will help you feel like you’re getting stronger?

- What’s your motivation for losing weight? Are you being held back from specific activities that you’d be able to do more easily if you lost a few pounds?

- How will you know if you’re becoming a better runner? Are you training for a race? Is your current technique making you injury prone, and therefore keeping you from doing other things you love to do?

These are the types of questions to ask yourself as you identify what your goals are.

Think about what’s important to you, and whether you’re able to do those things well now. Then think about what specific attributes would help you do those things better.

When you go through this process, you’ll likely discover that there are only one or two primary goals driving you. You may have other things you want to do, or other attributes you want to improve, but most of us have only a couple big picture goals pushing us forward.

Assessing and Prioritizing Your Needs

One way to assess yourself is to use locomotion to see what attributes are most lacking and need the most work.

Once you’ve identified the goals you’re working toward, it’s important to assess where you’re at so you can set up your periodization cycle to be most successful.

Assessment plays a big role in our programs so I’ll use one of those as an example.

Our foundational program, Elements, includes ongoing self-assessment. Going through the program will help you figure out which attribute the program addresses – strength, flexibility, or motor control – is the area where you need the most work.

That assessment of your needs helps you determine your next step.

Regardless of your goals, it’s important to do an appropriate assessment so that you can prioritize properly. After all:

“Priorities are like arms – if you think you have more than two, you’re crazy.” – Merlin Mann

You can’t prioritize 5 or 6 different things at once. It’s impossible. So figuring out where you need the most work and prioritizing accordingly is key.

I know assessing your own needs can sometimes be tricky, so if you need any help, get in touch and we’ll do our best to give you some direction (even if you’re not following one of our programs).

Planning Backwards

Dan John explains two perspectives for planning training cycles in his book, Intervention.

A big part of prioritizing, though, is doing some simple planning.

Dan John talks about this in his book Intervention. He says the most important thing in prioritizing your plan is knowing where you are now (Point A), and knowing where you want to go (Point B):

- From Point A: You have to see where you are now and what you need to do to make those steps toward your goal.

- From Point B: You have to look at the skill you want and work backwards from there looking at all the steps you need to attain in between.

You have to look at it from both sides. In looking backward, you can determine specific benchmarks in your training that need to be achieved before you hit that goal.

For instance, if you want to be able to do a muscle-up then you’ll need to be able to do a pull-up first. Then you’ll need to perform that pull-up with a false grip. You’ll also have to be able to do a dip from a full stretch position.

And so on.

In looking forward from where you are now, you have to figure out what is stopping you from making those steps. In the muscle-up example, you know you are having trouble with your pull-ups.

But what in particular is the problem? Most likely it’s your shoulder positioning and the muscles in your mid-back that need the most help. These specific issues are what you need to establish and plan for in the weeks ahead.

Working Around Challenges

The biggest challenge people run into is thinking you have to stick to the plan perfectly, or drop it.

Let’s say you’ve made your detailed and specific perfect plan.

- You worked through your first training block without any hiccups. Five weeks of conditioning work in the bag. Awesome!

- Now, you’re on your second training block. You’re two weeks in to a four week strength block when you suddenly come down with the flu. It knocks you out for a week.

Here’s where a lot of people get stuck.

Getting sick, going on vacation, etc. are things that happen. They’re part of the cycle of your life, and therefore, part of the cycle of your training. Taking a week or two off will not derail you.

When this happens, what I recommend is either picking up where you left off (so if you were two weeks into a four week block, just finish out the last two weeks); or you can just move on to the next block. There is no need to start that block or the entire cycle over again.

People often fall into that trap and they can wind up turning a 16-week program into a 6-month program. That’s simply not necessary.

Cycle Your Training with a Proven Curriculum

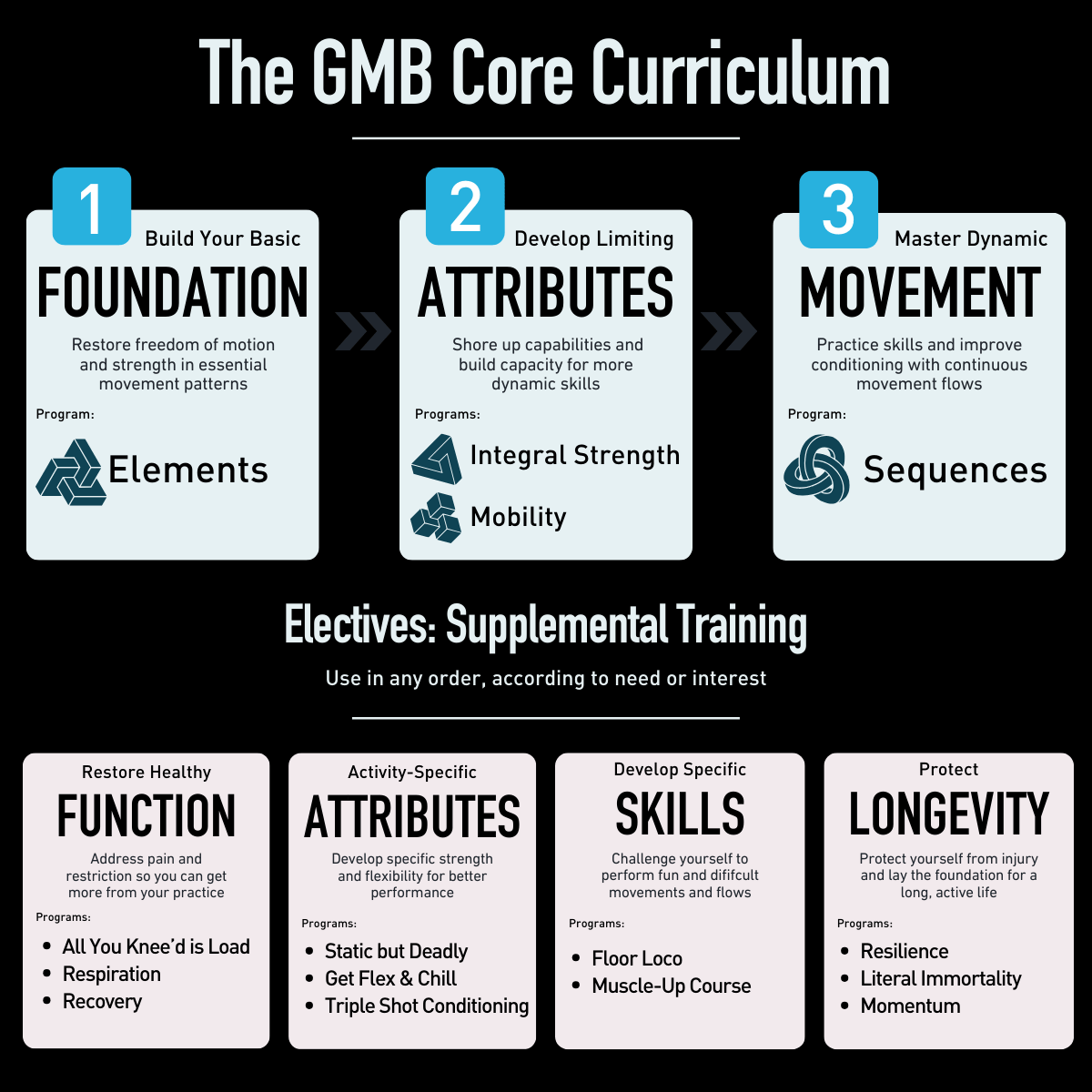

If periodization sounds complex (and it can be), you’re in luck – the GMB Curriculum is already designed around cycling your training:

It works like this:

Phase One: Restoration & Basic Movement

For most people, Elements is the best place to start because it helps restore natural range of motion and also builds strength and control in important movement patterns.

If you need specific work on an area with chronic pain, our Train Without Pain guide is also a great resource.

Phase Two: Capacity Building

Once your body is functional with a baseline of strength and skill, you can work to increase your capacity to move with strength and power.

The most important program here is Integral Strength, but many people combine that with Mobility to continue loosening up their bodies for more speed and power.

That might seem antithetical to the idea of cycling, but we carefully designed these programs to fit together as a set. Integral Strength will require rest days to allow for muscle growth, and Mobility is a low-intensity practice that won’t hinder that recovery. So the two actually complement each other in the same cycle.

Phase Three: Movement Mastery

After you’ve developed the capacity for powerful movement, you can train your body to move skillfully in a wider variety of movement patterns.

Sequences is our program for developing your dynamic agility through complex movements and flow routines.

Continued Cycling by Goal

From there, you can pursue whatever movements and activities interest you – confident that your body can handle whatever you throw at it.

Many clients choose to return to Elements of additional training cycles (some of them have done it over ten times!).

Others decide to repeat Integral Strength, maybe focusing on the bar or rings track to build even greater strength using different tools.

The truth is, once you’ve built a base of capability over several training cycles, you’ll have unlimited options.

As long as you work in cycles, you can progress indefinitely.

Find the Right Program for Your Next Training Cycle

See more about how all our programs fit together and find the best fit for your own goals: