Squatting is a fundamental position that, once upon a time, was a position of rest. But nowadays, many people lack the necessary flexibility and strength, and squatting has become a difficult task for lots of people.

While some advise spending as much time as possible developing the squat as a resting position, we’ve found it more useful to build mobility around the squat by treating it as a transition between other movements.

While some advise spending as much time as possible developing the squat as a resting position, we’ve found it more useful to build mobility around the squat by treating it as a transition between other movements.

In this article, I’ll show you what proper squat form looks like and give you the tools you need to get there.

First we’ll look at what’s holding you back from your “ideal” squat. Then I’ll help you troubleshoot, and give you a video tutorial that’s helped thousands of people get deeper and more solid in their squat.

Loosen All Your Major Joints

Get the quick routine that’s helped thousands of people move better with less pain, yours free.

Form Analysis – What’s the “Right” Form for Bodyweight Squats?

“Proper” squat form can vary based on who you are talking with, but the consensus points to the following:

If you can do a squat with exactly that form, great! But depending on your bodytype, congenital factors, and training history, forcing yourself into the above criteria may not be a great idea.

Working towards “ideal” form requires an analysis of particular factors:

- Flexibility in ankles, hips, knees, and low back

- Strength in knees and hips

- Hip joint structure

These factors affect the response to and timeframe needed for adaptation to physical training.

A Note on Barbell Squats

While we love weighted squats, this article pertains only to bodyweight squats.

First, to head off any objections from the barbell crowd, the information in this article pertains to an unloaded bodyweight squat.

Weighted squats, while of course having similarities with bodyweight squats, obviously have distinct requirements of their own. A bodyweight squat without load as mentioned above can be a position of rest, an exercise, and/or a transitional position. This is what we should keep in mind as we discuss the details of it.

If you want to work on your weighted squat, check out our article on how to improve your full body mobility for the overhead squat.

(For a ridiculously detailed exposition on the barbell squat see Greg Nuckols’s treatise here; it’s the best piece I’ve read on the barbell squat – it’s brilliant).

Flexibility Requirements for Bodyweight Squats

The first obvious concern with the bodyweight squat would be having adequate range of motion in your joints for the full bottom position. Flexibility restrictions are the most common barrier for people in their performance of the squat, so let’s take a look at what’s required.

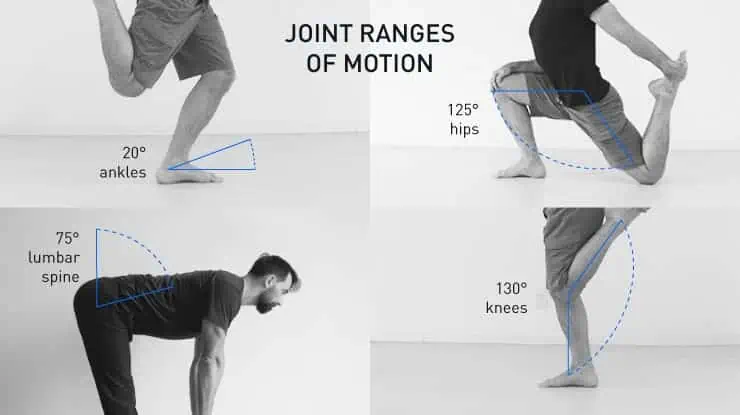

Normal Joint Ranges of Motion (ROMs)

Let’s look at the body areas most affected in bodyweight squats and the normative values ascribed to these joints. Here are the “normal” ranges of motion needed for a deep squat:

This isn’t bad information, but what’s “normal” is determined by a collection of data across the general population. In my opinion, “normal” doesn’t mean much of anything.

So what’s necessary for a full bottom squat?

It depends on your personal physical make up and the relationship between all your joints (as one can compensate for the shortcomings of another). For instance a lack of ankle dorsiflexion can be balanced out by more of a posterior tilt at the pelvis.

We’ll talk about this in more detail below.

Put Simply, Here’s What an “Ideal” Squat Takes

You don’t have to break out a goniometer and measure how far away you are from what you need. In our view, a great squat means that you have more ease and options for transitions into and in other movements.

Essentially, for the ideal squat described above you’ll need:

- Enough ankle mobility so that your knees pass over your toes 3 to 4 inches.

- Enough hip mobility so that your knees can contact your torso.

- The foot itself theoretically needs minimal motion in squatting, but anyone who has had a sprained foot or toe can tell you that it can definitely affect how you feel at the bottom of a squat, so improved mobility and strength in the feet will help.

- We would like an adequate amount of extension in the thoracic spine, as keeping the chest up allows you to go into other maneuvers. (A “flat” back actually requires a bit of spinal extension, as there is a normal kyphotic curve in the thoracic spine).

- You need a minimum amount of strength and motor control to keep the hips in neutral rotation to slightly externally rotated.

- Knee strength serves as a shock absorption. Trunk stability maintains upright posture.

Again, think of a squat as a transitional position rather than just sitting in one for as long as you can.

With all the talk of “sitting being the new smoking,” how is prolonged sitting in a squat any better than in a chair? For a more dynamic and enjoyable approach click here for Todd Hargrove’s audio lesson for a great example of how the squat is a transitional movement and working on it in that way can improve it.

What if You Don’t Have an “Ideal” Squat?

Well first you should realize that your ideal squat is not necessarily going to look like anyone else’s ideal squat. So you may not be as far off as you think.

Here’s a good example of how different one person’s bottom position squat can look from another’s. How are you judging which one is better than the others?:

These are all deep squats, but you can see they are different. One is not “more correct” than another; each person is just built differently.

With that said, if you are unable to sit in a squat comfortably and safely, there’s work to be done. Below we’ll go into more detail about progressing towards a comfortable deep squat, but here are some basic tips for addressing common issues in the squat:

Ankle Troubleshooting

- We have an extremely detailed article on the feet, ankles, and calves, in which we’ve included some calf stretches, along with strength and mobility exercises for the feet and stiff ankles. These will be best to work on for achieving the ankle mobility you’ll need for doing squats comfortably. Click here to see the article.

Hip Troubleshooting

- If tight hips are holding you back from getting a really good squat, our hip mobility routine will help you address the most commonly tight areas in the hips. Click here for our daily hip mobility routine.

Back Troubleshooting

- Our spinal mobility routine includes exercises that help with forward bending, backward bending, as well as all-around mobility. If your back tends to round out too much in the squat, these exercises can help. Click here for our spinal mobility routine.

Since these areas are the most common issues people run into, we’ve addressed them thoroughly in our introductory program, Elements, which has helped our clients improve their squats. Click here to learn more about Elements.

A Roadmap to Improving Your Squat

Now that we’ve looked closely at the squat, and examined the details that might be holding you back from being able to squat comfortably, we can now take a more global approach to fixing up your squat.

This video and the description following go through approaches you can take to improve your squat.

🎁 Get the 15-minute routine that’s helped thousands of people move better with less pain. Yours free. Just tell us where to send it.

Increasing Your Range of Motion

If you have trouble sitting down into the squat, you can work on increasing your range of motion starting from the ground up.

- Sit on floor with feet shoulder width apart. Do crab swings, by moving your butt back and forth between your feet and hands, increasing range of motion over time.

- Eventually you’ll move your hands and feet closer together, and work on pushing your butt through the heels as much as possible.

- Next you’ll walk your hands forward until you are in a squat position, and walk in and out of the squat.

- Finally, get into the squat and rock your body side-to-side and back and forth.

Work on Your Body Positioning

Once you’ve got enough range of motion to get into the squat position, you can start paying closer attention to how your body is aligned when getting into the squat.

- Foot Position–Your feet should be about shoulder width apart, turned out slightly, in the beginning. Eventually you want to be able to squat with the feet in any position.

- Back Position–Work on gradually straightening the back, and sitting back on your heels.

Use Props to Improve Your Squat Posture

Even if you’ve increased your range of motion, you may have trouble balancing yourself when lifting the chest and sitting back. This is when props can be very useful.

- Hold on to a doorframe or the edge of a wall at about hip height.

- Sit back as though you’re sitting into a chair, focusing on keeping the chest up and core engaged.

- Lower yourself into the full squat.

- Use the wall to help yourself stand straight up, rather than rounding forward to stand up.

Perfect Your Technique Without the Use of Props

Finally, once you’ve improved your balance and posture using a prop to assist you, you can start working on your technique without the help of the wall. Here are some technique cues:

- Keep feet shoulder width apart.

- Roll shoulders back and down, and with arms extended, point thumbs up.

- Sit the butt back as though you’re sitting into a chair.

- Keep the chest up.

- Maintaining that position, stand up straight by thinking of a rope pulling you through your head.

Programming Recommendations

Like anything you want to get better at, improving your squat takes dedicated time and effort.

That doesn’t mean you can’t work on other things at the same time, but making sure your squat practice is a consistent part of your routine for a while will help you tremendously.

I recommend using the following programming:

- Spend 10 minutes total on the stretches linked to above for the ankles, hips, and back. Choose 2 to 4 of the most difficult stretches.

- Then spend 10 minutes on whatever progressions you are up to from the video above. So, if you’ve worked through most of the Range of Motion section, but you’re up to the last step of rocking back and forth and side-to-side in the squat, spend 10 minutes on that.

You can follow this programming daily, and you can use this as a warm-up to your regular workout routine. Consistent practice is key when it comes to improving your squat, and you’ll find it won’t take long to start seeing some dramatic improvements.

Passively squatting for long periods of time, as many people recommend, is fine, but it’s really not the most efficient way to improve your squat.

Work on the stretches and exercises recommended, and you’ll see much faster improvement.

Next let’s look at some advanced squat variations…

What’s Next? Advanced Bodyweight Squat Progressions

While the basic squat is a fundamental movement, it can lead in to some more advanced exercises once you’ve built your foundation.

There’s no need to do any of these if they don’t fit your personal goals, but if you do aspire to be able to do some more advanced leg work, these are some of our favorite options once you’ve got the basic squat down.

Pistol Squat

The pistol squat is the most commonly practiced single-leg squat variation, but it’s also one of the most overcomplicated. Our detailed tutorial on the pistol squat takes a much simpler approach, kind of like the approach we showed in this basic squat tutorial–going from the bottom up.

The pistol squat is the most commonly practiced single-leg squat variation, but it’s also one of the most overcomplicated. Our detailed tutorial on the pistol squat takes a much simpler approach, kind of like the approach we showed in this basic squat tutorial–going from the bottom up.

Once you’ve got your basic squat down, the pistol squat is a great next step to work on.

Sissy Squat

The sissy squat is an old school bodybuilding exercise that gets too much flack for being “hard on the knees”. Yes if you aren’t prepared for it then it can be harmful, but that’s true of anything. Plenty of people derive great benefit from this exercise.

The sissy squat is an old school bodybuilding exercise that gets too much flack for being “hard on the knees”. Yes if you aren’t prepared for it then it can be harmful, but that’s true of anything. Plenty of people derive great benefit from this exercise.

This is included in our full article on bodyweight leg strength exercise. Click here to see it in action.

Peacock Squat

The peacock squat (AKA the dragon squat) is an exercise taught at many of our GMB Seminars, and it’s also something we’ve covered in detail for our online community, Alpha Posse.

The peacock squat (AKA the dragon squat) is an exercise taught at many of our GMB Seminars, and it’s also something we’ve covered in detail for our online community, Alpha Posse.

It involves crossing the leg behind the body, and then spinning the body on the balls of the feet to face the other direction. Because of this, the peacock squat is also great for improving body control and proprioception.

Shrimp Squat

The shrimp squat is a favorite single leg squat variation because it is a great challenge for your balance, strength, and control in the end-ranges.

The shrimp squat is a favorite single leg squat variation because it is a great challenge for your balance, strength, and control in the end-ranges.

The shrimp squat is taught in our Integral Strength program, taking you from the most basic progression to the full exercise. The nice thing about the shrimp squat is that, although the most advanced variation is quite tough, the earlier progressions are very accessible as long as you have a basic squat already.

Here’s a comparison of the shrimp and pistol squat to help you determine which is best you for.

Prime Your Body to Squat Well and Do Anything Else Wanna Do

The ability to squat comfortably may not be a flashy skill, but it is incredibly helpful for moving freely and easily throughout your life.

Learning to squat will inadvertently help you with other skills, both athletic and practical. Think of every time you squat down to pick something up off the floor. A comfy squat makes this so much easier on yourself.

To be clear, learning how to squat well is just one way of moving better and performing the way you want.

We teach the squat, along with 4 animal movements in our best-selling program Elements, so you can build full body strength, mobility, and control.

Get Deeper and Stronger in Your Squat

Elements teaches you 4 movement patterns most workouts neglect that build strength and mobility for squats and much more. Check it out ⤵️

I'm AMAZED at how much my active mobility has improved in just 3 weeks of Elements.

After years of training like a powerlifter, I developed neck and shoulder pain. My hips, hamstrings, and calves have felt tight for as long as I can remember, and I had terrible mobility through my shoulders and upper back as well. I wanted to improve my overall mobility and body control and build the foundation for more complex skills down the road. Essentially, I wanted to become the master of my body.

Since starting Elements I no longer have chronic tension in my neck; my shoulders move better-than-ever (no more popping or clicking when I do shoulder circles); and getting into deep squats feel effortless now (even without a long warm-up or spending hours per week "foam rolling"). I feel so much more in control of my body, and feel like my body has a lot more options for moving around now. It's incredibly fun to "explore" those movement options and just play!