As a trainer, your experience and knowledge will surpass that of most of your client base.

This is a double-edged sword because on one hand, you have the knowledge that comes from all that experience. And that’s helpful for doing your job.

But on the other hand, you might suffer from the ‘curse of knowledge’ which means you tend to:

- Assume someone else ‘gets it’ when you communicate a complex training idea because you’ve internalized it.

- Not follow your own rules because you ‘know your body’ and feel you can push through something you might never recommend to a client.

In this article, we’re giving you three ideas that will help you better communicate the concept of autoregulation to your clients and be the example they need to learn from.

“No pain, no gain” is almost always a bad idea

You know this in your gut. And it might be something you tell your clients. But do they understand why? Are you doing a good job explaining it to them?

You know this in your gut. And it might be something you tell your clients. But do they understand why? Are you doing a good job explaining it to them?

Many of the fitness marketing messages around us are full of go hard or go home slogans that encourage sacrificing your body for a favorable outcome.

And while this type of mentality *might* work for the most advanced athletes, it’s definitely not sound advice for the average person with a desk job, family, life stressors, and a mortgage.

But this message gets repeated, and it’s ingrained into exercise culture. There’s a type of fear built-in to many fitness messages because we are more apt to acting when we fear that we’ll miss out.

Things like…

- “If you don’t do cardio, you will have heart problems.”

- “Worried about getting fat? Better skip those carbs and eat your protein.”

- “Didn’t go to failure on every movement and lie in a puddle of sweat at the end of your workout? You must not be working hard enough.”

This is the paradox of human motivation. We are driven by pain or gain, and many of us would rather do something to avoid pain than make incredible gains in the future.

Those messages make you feel as if you’re not doing enough. But what about the opposite? Do cardio because it makes you feel good. Eat carbs because they’re essential for a healthy diet.

Push yourself during your workouts so you can make improvements over time, instead of punishing yourself.

While those messages of improvement sound great, they don’t sting as much as the negatively-focused messages that spur us to act.

It’s easy to understand this stuff, but much harder to apply. Even GMB trainers struggle to pump the brakes sometimes.

How do we handle that? Autoregulation.

This is a tricky concept for everyone because of influence. Many of us were exposed to training concepts through mass media, and with that always comes a marketing message.

Usually something like “feel the burn” or “winners never quit and quitters never win,” so it’s easy to understand if you don’t have a gear outside of “I’m gonna punish myself in the gym today.”

Even those of us rich with athletic backgrounds struggle to tame our egos.

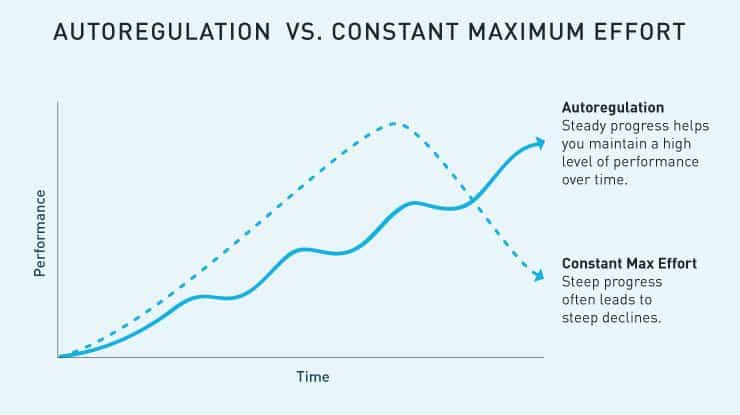

Autoregulating your training is a far cry from what you’ll see in the gym. Most people coming to us have a history of pushing their bodies to the point of exhaustion, and sometimes injury.

After all, when you’ve been told that going to failure and sweating heavy is what gets results, doing the opposite is how you become mediocre, right?

That’s what most people believe, even if they’ve never been asked about it.

And when you bring up a concept like autoregulation, and explain to someone that they don’t have to take their body to the max every session, you might get some pushback.

🚨 By the way, even our trainer candidates in the GMB Apprenticeship struggle with learning autoregulation at first. It’s an easy concept to understand, but a difficult one to internalize and implement.

They probably won’t believe you, at first, when you tell them they can ease up on a movement and work on it slowly until they get it right.

Or that they can stop when it feels like it’s too difficult.

It’s important to help them understand that doing something well is always about doing it properly. Making sure it’s quality, even if that means taking more time and doing fewer reps.

The typical approach is to push yourself to a point of exhaustion so you *feel* the workouts. But overexerting yourself almost always results in bad form, and in some cases, injuries.

So what’s the best way to make sure you teach them how to slow down and do the movements with focus? You learn to do it with your own workouts.

While you might get the concept on paper, truly understanding it means applying the principles in your own training when you’re all by yourself.

Be honest with yourself. How much attention are you paying to your sessions?

Specifically, this means:

- Being mindful of how you feel* at the start of a workout and adapting accordingly.

- Monitoring your performance in terms of quality as well as reps/volume.

- Pulling back on intensity and taking rest days as needed.

- Placing training consistency and longevity over rapid skill acquisition and overexercising.

- Not working through pain even if that means you don’t do specific exercises in your program.

*Autoregulation and mindfulness isn’t just about how you feel.

How you feel going into a training session won’t always affect your performance. You shouldn’t adjust your training on the fly because you feel a certain way.

Autoregulation works best when you adapt your training based on your actual performance.

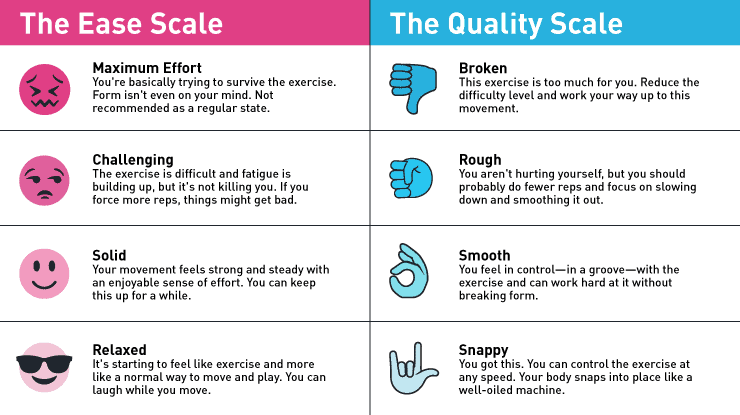

Making a habit of rating the quality of ease of movements will help you keep track of how well you’re doing beyond the simple black-and-white of completing a certain number of reps. It also helps you get acquainted with the valuable biofeedback that’s always been there.

For example, if you get warmed up and start working on a movement that you’ve been practicing for weeks and it’s noticeably more difficult, this is critical biofeedback.

Most people ignore this message and simply proceed with the training. Then they push themselves using subpar form, which reinforces less optimal movement patterns. And if they’re not careful, they could inhibit recovery or injure themselves trying to push for an intensity that should’ve been dialed back.

The trick is learning how to observe what your body needs and then doing something about it.

We teach this as part of the 5P Framework in the GMB Method:

What you’ll pay attention to is how your body is responding to the Practice phase after you’ve done your Preparation. Other parts of the session matter too, but the transition form Prep to Practice is usually where you have enough info to make the right decision and before you’re committed to a certain plan. Trying to judge your readiness before even starting can also be deceptive.

If you’re not feeling as strong as before and the movements are harder than you remember, it’s a sign that you should ease up on the intensity, at least for this session. Go through the motions, work on your form, but don’t push yourself if you’re not up for it.

✋🏻 Critical Coaching Questions:

- How can you practice autoregulation to ensure you internalize the concept and utilize it in your own training?

- And then how can you use your experience to help your client understand it?

Why your example matters more than what you say

Don’t just talk about how training through injuries or sickness or when overly sore is off limits. Be about it.

If you tell your clients to do something but you do the opposite, why is that?

For example, if you tell them they need ample rest days to recover and make progress, but you never take a day off, is that the message you want to send?

Our clients come to us for multiple reasons. They believe we can help them achieve their exercise and fitness goals, and they trust and respect us enough to take our advice.

But deep down, they need a model for what a safe, healthy, and progressive movement practice looks like in real life.

If you’re constantly getting injured, or putting yourself at risk for the sake of making gains, what is this teaching your clients?

Most of your customers will aspire to your level of ability. The best way to help them get there is by building good training habits, and encouraging them to take a longterm approach that will keep them healthy and able to make progress for years.

✋🏻 Critical Coaching Questions:

- What are you doing to be the example your clients need?

- How have you shown up in the past that suggested you were talking the talk but not walking the walk?

Teaching your clients about longevity of training

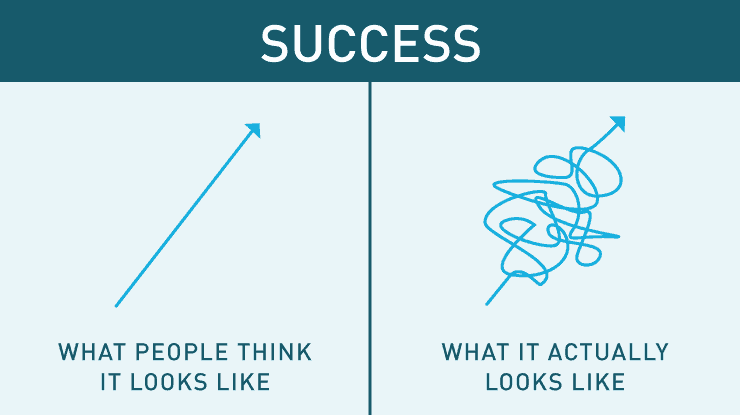

Lots of our clients think once they hire a trainer, the path to their goals will be straight and narrow. However, you know long term progress is anything but linear.

A belief many of clients have is that if they don’t push themselves to their max, a training session wasn’t effective. And this approach to training creates a lot of frustration and can breed some internal guilt for not “working hard enough.”

But as a trainer, you know that consistency is far more important than any single effort. Results come from repeated exposure to similar movements over time, and it’s your job to help your clients understand this.

What good is a hard training session if you’re too sore or injured to work out the rest of the week?

Just because you don’t have the energy or motivation to push yourself to the max doesn’t mean you can’t get an effective training session in.

As you know, in our programs, we give you the autonomy to make a decision after your warm-up. Do you feel good enough to push for a challenging session? Or do you feel stiff and need to take it easy?

Whatever you choose is up to you, and both decisions are correct.

✋🏻 Critical Coaching Questions:

- In what ways can you give your clients examples of how autoregulation plays into their longterm progress and success?

- What would you do to help them break out of the black and white mindset of having to push themselves too hard too often?

Learn to Coach Your Clients Systematically

Most of us got into training others because we enjoy training ourselves… and we learned the hard way about all the pitfalls and mistakes that can slow our clients’ progress. As a result, we develop a lot of intuition around the right ways to train.

But our clients deserve more than lucky guesses. Coaching isn’t voodoo.

Yes, there’s an art to it, and that hard-won intuition and experience matters. But just like learning to auto-regulate the intensity of your training, if you don’t track your performance and follow some kind of system, it’s easy to fall into the trap of just doing whatever you feel like, and that’s not a recipe for progress.

That’s why we systematized our GMB Method and teach it as part of our certification and apprenticeship process.

Develop Your Coaching Skills

GMB’s Apprenticeship program offers an in-depth look – in both theory and praxis – at the pedagogy behind our core curriculum of programs. It’s required for certification in the GMB Method.