We all know that muscular strength is important, but what about your tendons and ligaments?

Though muscle development is relatively straightforward, most of us only think about our connective tissues when they bother us.

And unfortunately, tendons and ligaments can be less conditioned for the activities that we ask of them, especially for those of us doing repetitive movements under load.

But even if you haven’t had any problems so far, it’s important to take good care of your connective tissue. Tendons can take longer to bounce back than muscle, so dealing with tendonitis can set you back from your progress for a frustratingly longer time than you’d like.

This resource covers basic tendon anatomy, specific exercises for building strength and resilience in key joints, and steps you can take if you’re in pain (including a book recommendation). There’s lot here, so bookmark this page and use the links below to navigate.

Guide to Tendon Strength & Health

How Tendons and Connective Tissue Work

Tendon strength in the vernacular is sometimes meant as an explanation for how skinny “wiry” people demonstrate high levels of strength on par or greater than someone who is more obviously well-muscled. The assumption is that bigger muscles mean more strength (which is true to an extent) and if a person doesn’t have the appearance of big bulky muscles, then their strength must not be from their muscles.

Hence, we hear talk of “tendon strength.”

And of course, it’s a myth.

Muscles are the body tissues that generate tension and strength not tendons (or ligaments). This strength does come directly from muscular size, wherein a bigger muscle has the capability of being stronger than if it were smaller, but there are other factors contributing to the demonstration of strength. Particularly how adept a person is at a specific feat of strength. And that is directly correlated with how practiced and familiar you are with that demonstration of strength.

What are Tendons?

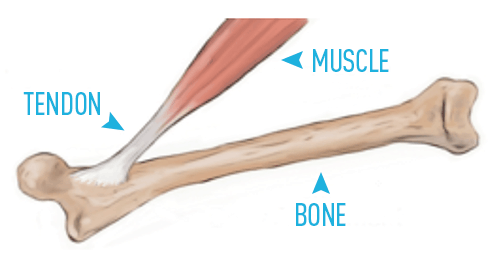

Tendons are connective tissue that attach muscle to bone, as opposed to ligaments which connect bone to bone.

And if that more heavily muscled person were to start learning and practicing how to wield that tool, then they would soon attain that skill and perhaps surpass your ability because of the potential of those bigger muscles.

Another reason why there may appear to be a “tendon strength” phenomena are the common tendon injuries in sports, repetitive use activities, etc. which are distinctive from muscular sprains. It would make sense to ask if tendons themselves can be strengthened distinctly from strengthening muscles.

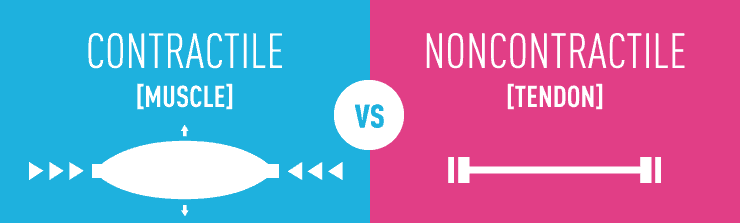

The apparent susceptibility towards injury of tendons occurs because of the differences of how tendons and muscles are comprised. Skeletal muscles are what as known as “contractile tissues”, meaning they can generate movement within themselves (the fibers pull against each other and shorten the overall muscle length), while tendons don’t have that capability. Those tissues have the property to resist forces but do not generate them on their own.

But they are much more than just pieces of stiff rope, tendons have elasticity, an ability to stretch with capabilities of storing and rebounding force. Such as in our achilles tendons which have a kind of “bounce” but this strength is more passive, that is a force has to be applied to them. In the case of the achilles this is the force from your muscles above and the reactive force from the ground below.

Contractile vs Noncontractile Tissues

Muscle are primarily composed of tissue fibers that can create movement (sarcomeres). On the other hand, tendons are primarily composed of collagen; a protein that doesn’t create movement but is resistant to both compression and tension (pulling) forces.

Are there different protocols and exercises that would target tendons specifically rather than muscle?

Theoretically yes, but in real world practice this doesn’t really happen.

The same forces and stimulus used to improve muscular strength would be needed to improve tendon strength. Changes in the tendon just occurs more slowly. It’s similar -but a bit longer- to the timeframe of building bone. Changes in muscular strength often outpaces tissue changes in the tendon, especially so when using performance enhancing drugs.

This is seen with the unfortunately common injuries of tendon ruptures in anabolic steroid users. Their muscles became capable of generating force greater than the tendon could handle.

This also applies to the common query of whether there are specific ways to strengthen joints, again in distinction from strengthening muscle.

Strictly speaking, the answer is “no.”

But while joint mobility training doesn’t technically strengthen connective tissue, when considering training holistically these improvements can help.

When you improve your range of motion and your control over those ranges of motion, there is a better distribution of forces and tension through your joints. This along with muscle strengthening work produces healthier and stronger joints.

How Do You Strengthen Tendons?

It would be facetious to give the too simple advice of “just train your muscles and you’ll be fine” when answering the question of how to improve tendon strength. It’s a legitimate question and there are absolutely ways to address that concern.

Just as discussed above, we have to ask ourselves what it is that people are actually referring to when they ask about tendon strength? It’s a fair bet that they are really asking about how to be more resilient and stronger at their joints, both to be less prone to injury and also to perform better in the physical activities that they enjoy.

Framed in this way, asking how to improve tendon strength is a great question! And then it becomes an easier question to answer and give advice that would be valuable. A couple of concepts can help us talk about some practical tips to help you.

Movement Variability for Joint Health

Being able to perform/be conditioned to a variety of movement patterns is an important key to physical autonomy.

Our bodies in their efficiencies generally conserve and distribute resources as dictated by our environment, a term I’m using as the milieu of everything that our bodies experience. What we habitually do physically, our diets, the climate where we live. Our bodies (and minds) will always “regress to the mean”, the path of least resistance is the most efficient use of our body’s resources and homeostasis is the ever-present goal.

This, like most complex things, can be both good and deleterious. Good for the economical maintenance of steady health and performance, because it generally takes larger perturbations in our environment to change our bodies.

We know the stimulus for building strength or improving mobility, and increasing our stamina has to be above a certain threshold. And in the other direction, tissue breakdown and injuries have to be significant as well to disrupt this balance. But it also means that we are nearly always dancing on the edge of improvement or breaking down.

In training for health and fitness, improvements and injuries are different sides of the same scale.

This is why play and exploration in the many different ways we can move has been an ongoing motif in the GMB Method. The more movement variability we have and condition ourselves to perform, the more our bodies build tolerance to the many different physical forces we encounter and they become much less disruptive and injurious.

You do have to be a specialist to be excellent at something, but it can be a detriment to your overall health and well being. The vast majority of us are not even close to the level of professional athletes so we shouldn’t get hung up on optimizing. Get at a decent level of comfort in a variety of movements and you’ll be much better off than trying to get exceptional at one or two patterns.

That’s much better for our overall health and fitness in the totality of our lives, not just for a weekend competition.

Developing Healthy Joint Alignments

It’s best, in both health and performance, to distribute and create forces with the body as one unit.

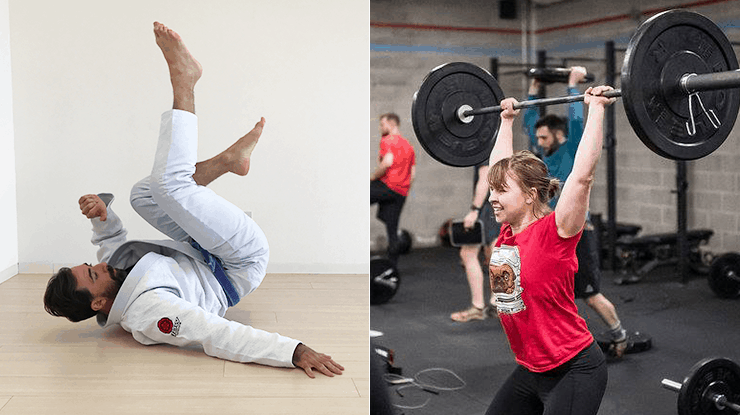

Martial arts, throwing sports, and weightlifting seem very different but at their core they demonstrate the importance of body alignment and proper technique. These are paramount for the best expression of your strength and power. Small deviations and “leaks” in your alignment are essentially a waste of your energy.

These alignments and good form also tend to be most advantageous for receiving forces. Overuse and repetitive strain injuries at the tendon (and ligament) are from a combination of decreased conditioning of the tissues and poor ergonomics, which I’ll define here as movement efficiencies. I say a combination because you really can train yourself for anything, there are a lot of examples of heavy work laborers and professional athletes that can sustain and perform well in “poor postures” simply because they’ve conditioned themselves to do so over a long period of time.

But unfortunately, less than appropriate alignments and movement inefficiencies tend to catch up with you as time goes by, and “the bills come due” in the form of nagging injuries and pain complaints.

Improved alignments also go hand in hand with tolerating changes in speed. Sometimes things happen fast! Conditioning yourself to maintain good body alignments while progressively adapting to faster speeds is a significant part of being resilient to stress and strain.

We can do these things in a multitude of ways, and good athletic and sport training employ these principles as part of an optimal comprehensive program.

- Heavier progressive loading (weights, advanced bodyweight exercise)

- Technique/form drills (martial arts stance training, sport specific technique drills)

- Dynamic variable speed training (gradually progressive plyometrics, bounding, jumping)

These types of training are likely very familiar to you if you’ve done any sport training, whether they were sprinkled in randomly or hopefully part of a well thought out progressive training regimen. So with all this said, I posit that a variety of training methods would be best for tendon health and strength.

As with all good fitness programming, it very much depends upon your current condition (your training status and injury status and history).

If you are nursing an injury and currently have pain or conditions such as tendonitis, then you should approach your exercise regimen much differently than if you are feeling great and have several months of consistent good training behind you. To make this more useful and less convoluted let’s start with some examples for the latter, and assume you aren’t dealing with any significant tendon/joint issues.

If you are, feel free to head over to where we discuss dealing with Pain & Tendonitis.

Exercises for Shoulder Connective Tissues

Shoulder complaints were extremely prevalent in my years of practicing physical therapy.

Rotator cuff and bicep tendons, A-C joint ligaments, and other tissues in this complex joint all experience stresses from both sports and everyday activities such as reaching and lifting overhead. Aside from traumatic injuries, the most common causes of the complaints were from not being able to tolerate these repetitive stresses, people were simply not conditioned enough to deal with what the activities they wanted or required to do.

Once basic strength was improved, we moved on to exercises like the ones below.

Shoulder Swings

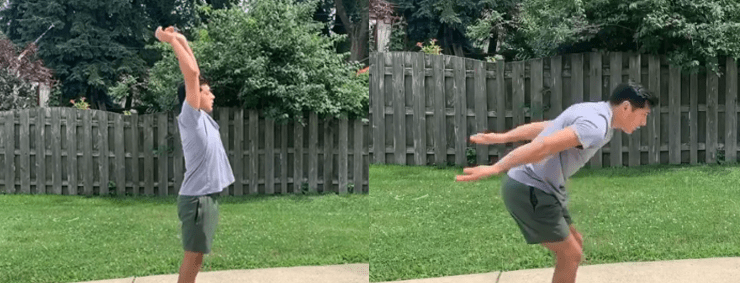

These movements are a good demonstration of introducing ballistic work while emphasizing the concept of appropriate body alignments. I was reminded of these and incorporated them into my training last year from the instruction of my baguazhang teacher Carsten Stausberg

When you perform these, use your lower body and trunk to drive the speed of the swinging and relax your shoulders and arms. Start at slower speeds and increase very gradually. Not only is this necessary to prevent strains and sprains but also because you need repetition and practice to find the appropriate alignments that are best for your body and its current condition. For both of these reasons forcing yourself does no good at all!

- 1. Both hands swinging up overhead

- 2. One hand swinging up overhead

- 3. One hand swinging at angle to side and behind

- 4. One hand swing at angle in front and to the side

Start with slower velocities for 1 to 2 sets of 10, and progress to faster swings for 2 to 3 sets of 20 each.

Hanging Side to Side Swaying

Here you are working on traction loading on the tissues of the shoulder in a combination of vectors (straight down to the ground and laterally). Again start with less intensity and time. A good rule of thumb is to do half as much as you think you can! It’s much better to do less and then gradually increase than to overdo it and hurt yourself.

Start with your feet on the ground (or other solid supportive object) to take some of your weight off, and with 1 to 2 sets of 20 seconds. Progress to faster swinging with more of your weight and longer times of 2 to 3 sets of a minute.

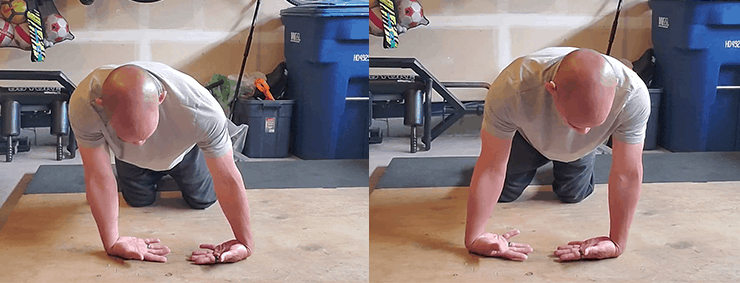

Pushup Plyometrics

These are classic exercises that are intended to improve upper body power and speed, and they also have the benefit of improving your tolerance for speed changes and also your understanding of alignments.

- 1. Both hands

- 2. One hand

As always the caveats of gradual progressions in speed, intensity, and volume should be heeded. And though you may be able to do them from a full push-up position, I’d recommend for the purposes of tendon strengthening that you do these from the knees. This will allow you to do more repetitions and also modulate your intensity so you can feel and learn from the movement much better.

Start with slower velocities for 1 to 2 sets of 5 and progress to faster for 2 to 3 sets of 10.

🎙️ Related Podcast: Shoulder Mobility for Less Pain

Exercises for Preventing Wrist and Elbow Tendonitis

Wrist and elbow complaints are incredibly common and I think are a big part of the reason why people ask about improving tendon/ligament strength. Lingering pain in these areas is so disruptive!

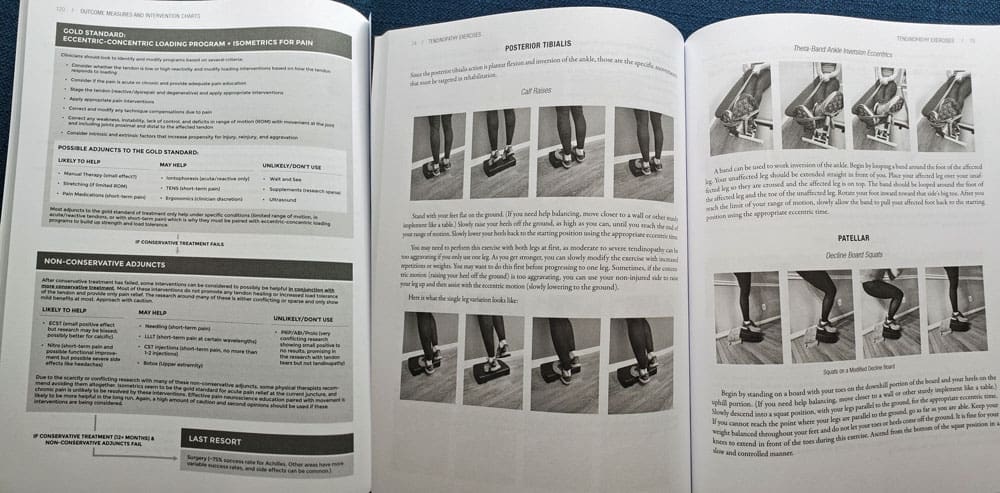

Backhand Weight Shifts

The wrist and elbow are intimately connected so this positioning affects both. The wrist extensor complex is implicated in “tennis elbow” (lateral epicondylitis). Use padding as necessary and shift your weight back toward your hips more at first, then gradually increase the weight through your hands. Concentrate on how you feel during the holds and the weight shift, and be ready to constantly adjust as needed.

There’s a fine balance between stimulation and overdoing it. This takes trial and error but is a great lesson and applies to all of your training in general. Use this exercise as an opportunity to learn!

Start with less weight on your hands for 1 to 2 sets of 20 seconds and progress to more weight for 2 to 3 sets of 1 minute.

Wrist Flexor Plyometrics

This exercise works on the wrist flexor complex. This is associated with medial epicondylitis, the so-called “golfer’s elbow” and a common area of complaint in people that begin to do more pull-up training than they are conditioned for.

Emphasize landing and pushing off your fingertips with control.

Start with less weight on your hands for 1 to 2 sets of 5 and progress to more weight and 2 to 3 sets of 10.

Pronated drop and grab

This is another classic exercise that is helpful for improving wrist extensor complex load and speed tolerance. You can use anything from a weight plate to a weighted ball. But definitely start lighter than you think!

Start with less weight for 1 to 2 sets of 5 and progress to more weight and 2 to 3 sets of 10.

Pushup plyometrics

The same pushup plyometrics are also effective for the wrist and elbows.

🎙️ Related Podcast: Exercises for Wrist Strength

Exercises for Knee and Ankle Tendon Strength

Achilles and patellar complaints are also very common especially in people getting back into, or overdoing, activities that involve running and direction changes (soccer, basketball, etc). There is tremendous benefit to conditioning the tissues to handle loads in various positions with increased speeds.

⚠️ This cannot be repeated enough: these exercises need to be incrementally progressed and very likely at a slower pace than you’d like!

When we share movements and exercises similar to these on social media there are invariably comments such as “my knees would explode if I did this!” Well then you probably shouldn’t be doing this exactly as shown. There’s a context for every exercise and perhaps a particular one isn’t applicable to you but will be very useful for someone else.

Bouncing Split Squats

Begin with an even weight distribution but as you get used to the movement, shift more onto the back leg. In this way it places more force on one knee and ankle.

Start with less weight on the back leg for 1 to 2 sets of 5 and progress to more weight shift and 2 to 3 sets of 10.

Hop, Stop, and Drop

This is an example of a movement that shows the interplay between muscle and connective tissue in demonstrating resilience and durability. Which, notwithstanding the actual biology of tendon strength, is I think what people are getting at when they ask about developing tendon/ligament strength.

It’s actually a simple movement, do a small jump, land on the ball of your foot and drop down to place your knee on the ground. But there’s a lot in there!

Can you control the landing on your foot? Are you wobbly at your knee and/or ankle? Are you retaining your balance? Can you control the descent to place your knee on the ground gently?

This exercise is a good barometer of your lower body’s capability to maintain appropriate alignments and control under load and speed.

Start with shorter and slower hops, and perhaps don’t drop your knee down all the way to the ground, for 1 to 2 sets of 5. Progress to longer and faster hops for 2 to 3 sets of 10.

Ankle Bounces

Ankle sprains and tendon problems are invariably the result of decreased tolerance for repetitive loading and speed changes. Which exactly describes the running and cutting back and forth that happens in nearly all sports.

These ballistic exercises allow you to modulate loading and speed so you can concentrate on how the alignments feel and how your body reacts to them.

1. Standing on ground: both legs, one leg

2. Standing on elevation: both legs, one leg

Start with 1 to 2 sets of 10 to 15 and progress to 2 to 3 sets of 20 to 30.

🎙️ Related Podcast: Ankle & Foot Health

Overcoming Tendonitis: What If You Are in Pain?

The previous exercises are examples of the types of exercises that are useful for improving your whole body resilience, particularly at the muscle/tendon system, and integrating appropriate alignments with progressive movement variability and speed tolerance.

But what if you are injured or in pain? Though some of them you could do with some adjustments in intensity, it’d be better to start with fundamental rehabilitation style training and progress from there.

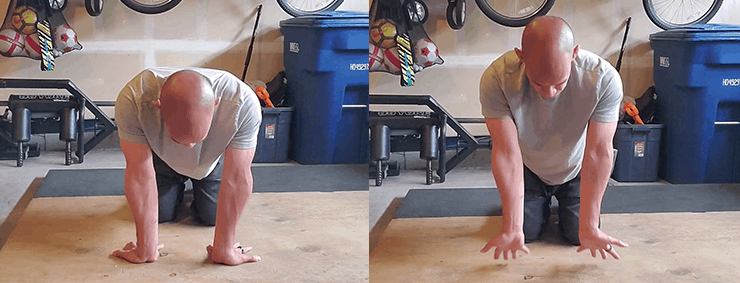

This is covered comprehensively in Overcoming Tendonitis.

Steven Low is well known in the bodyweight fitness community for his work in Overcoming Gravity, which is often referred to as a seminal text on everything bodyweight exercise. It’s a massive book that earns its popularity with personal trainers, coaches, and just plain exercise geeks!

Steven Low is well known in the bodyweight fitness community for his work in Overcoming Gravity, which is often referred to as a seminal text on everything bodyweight exercise. It’s a massive book that earns its popularity with personal trainers, coaches, and just plain exercise geeks!

Low and his colleague Frank Skretch bring that same attention to detail to connective tissue health in this book, which is essential reading if you are experiencing tendonitis symptoms and want to get out of pain.

It’s relatively slim at 124 pages (not including bibliography and notes), but those 124 pages are packed with information. In fact it can be daunting to someone without a scientific or medical background.

As a comprehensive text it’s meant to address the many aspects of a complex condition, which makes it necessarily technical. This is not to say that you need to be a health care professional in order to read it, but in my opinion the “layman” reader should feel free to skim through the denser parts and focus on the overall points and the exercise and treatment suggestions. Rehab professionals and personal trainers that specialize in this type of work would benefit greatly from reading it thoroughly from cover to cover.

A nice option would be for clients to suggest/purchase the book for their health care provider and/or personal trainer.

The book begins with an important overview of how to read research in general, which is necessary when looking at things with the evidence-based mindset. Again, this is another complicated subject but knowing the fundamentals allows the reader to understand what studies and research would be meaningful to them. This goes beyond tendonitis and applies to all research in general. In my opinion, being even just a little literate in this would improve everyone’s lives.

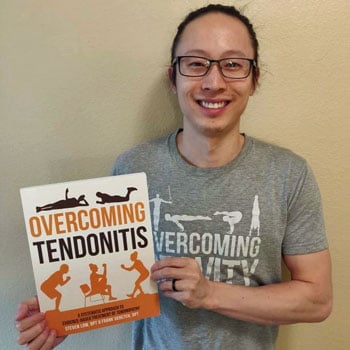

They then go into the history and current knowledge of tendonitis/tendinopathy, the myths surrounding the condition, and the details of how to approach exercise and training. These are the technically dense topics I mentioned earlier and again it wouldn’t hurt to skim through them if you feel overwhelmed.

The rest of the book is where you’ll learn exercises, their progressions in a good rehabilitation plan, and a great review of other therapeutic interventions such as injections, laser therapy, and others.

The authors have provided an excellent and thorough compendium here and in my opinion is worth more than the price of the book. The development of a rehab plan requires a lot of trial and error and continual assessment, but the text gives you a great blueprint to guide you (or your trainer/therapist).

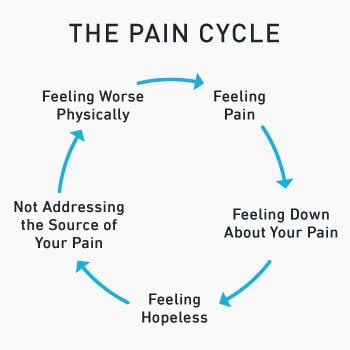

I won’t do a list of all that’s in this part of the book but I do want to talk about an incredibly important topic that’s also covered, – it is also a part of the podcast conversation I had with Steven that will be released soon! – which is a discussion of pain. The pain science and education over the last twenty years has dispelled a lot of myths that we carry with us, and has helped so many people to finally break free from their own cycle of pain.

Breaking Free from Chronic Pain

I’ve written before about the complexity of chronic pain, and one aspect that can’t be repeated enough is the fact that tissue damage does not necessarily correlate with pain.

I know this is absolutely counterintuitive when we first hear this, it was to me when I first learned it! But there are a multitude of studies that show this over and over again.

I’ve written before about the complexity of chronic pain, and one aspect that can’t be repeated enough is the fact that tissue damage does not necessarily correlate with pain.

I know this is absolutely counterintuitive when we first hear this, it was to me when I first learned it! But there are a multitude of studies that show this over and over again.

People with minimal or no complaints at all have MRI reports of clearly degenerative spines and scans of frayed tendons hanging on by a thread. The other side of this is when people have debilitating pain but their x-rays and scans reveal no damage.

One thing to get out of the way is that this does not mean that pain is all in your head. This is absolutely not true and is unhelpful. It simply means that pain does not go hand in hand with tissue damage.

Pain exists and we know it exists. There is clear evidence of nervous system increased sensitivity. With ongoing pain, these sensitivities can occur both in the nerves at the site of pain (peripheral sensitization) and in how our brains react to inputs (central sensitization) where what should be an innocuous sensation is interpreted as very painful. This is shown in functional MRI’s where areas of the brain “light up” when a person experiences pain, even long after the injury has healed.

Let’s take an ankle sprain for example, at the time of injury when there was that initial pain, certain receptors multiplied because those particular sensation inputs began to outnumber others, such as temperature and movement. And when they outnumber those others they become more sensitive to when that input happened. It’s a bit like turning up a microphone so that your voice is super loud when you talk into it.

This is very real and very much not “all in your head.”

I feel that this is a very empowering thing to know, as it allows us not to get hung up on the damage that is shown in our x-rays or MRI’s or when doctors tell us our joints are “bone on bone.” That may be so, but it does not consign us to never-ending pain.

And perhaps that’s the primary benefit of this book, to show the research and the experience that has taken even people with very damaged tendons out of their pain and back to the activities they love. What a wonderful thing.

To take this back to advice on what to do if you have tendon issues, the exercises we shared above are best for when you have no current problems or for when you are at the point when you can do more without flaring up your symptoms. They are a great segue to participating in more intense training.

If you are currently in pain and don’t have that tolerance yet, start with a progressive rehab plan that often begins with isometrics, and lighter load which then increases in intensity and variability. Overcoming Tendonitis is a great resource for that if you are not already under the guidance of a health care professional.

Resources for Overcoming Joint & Tendon Pain or Injury

Over the years, we’ve created detailed guides to restoring healthy, pain-free function to all the major joints in the body.

Comprehensive Joint Health Guides

- Neck Exercises for Pain & Tension

- Strength & Mobility for Shoulder Pain

- Guide to Addressing Elbow Pain

- Spinal Health & Mobility Exercise

- Hip Exercises for Power & Mobility

- Exercises for Knee Pain

- Guide to Healthy Feet & Ankles

- 💌 Get a downloadable version of all these guides sent to your email

And if you’re dealing with persistent soreness in your joints, I highly recommend picking up Overcoming Tendonitis.

Don’t Neglect Tendon and Connective Tissue Health

It’s natural to focus on strength and skills. We can see and feel those.

We can see our muscles growing and feel the difference when we pick up something heavy or move quickly. We can see ourselves performing skills and feel that they get easier with practice.

But with our tendons and ligaments, the only way we know they’re not getting stronger is when we notice pain, and by then, we’re already behind the eight ball. Since tendon pain can take a long time to recover from, it’s important to address tissue health before you develop a progress-killing case of tendonitis.

The exercises in this article will help.

Another way keep your joints healthy is to make sure to include regular connective tissue exercise for all your major joints in various ranges of motion. Our Resilience program is one option.